Lit only by the three candles you carry, the shadows in the hallway draw long. Outside your tiny circle of light, there is movement. You cannot tell if it’s the wind playing with a curtain, your candles’ flame playing with the shadow, or something else all entirely. The hallway was at one point richly appointed, but a creepy decay has sunken into the very bones of the building around you. The carpet was red once, but its shade has leeched out of it and the edges are fraying as if chewed upon by invisible rats.

Every step sends a muffled creak beneath you, and yet the sound refuses to echo. Only your breath, short and shallow, seems to carry off into the night. Step by step, you creep towards the edge of your light, pushing it out in front. Fear grips your heart in an icy vise, and even your blood seems sluggish in your veins. Yet you push forward. No, not pushed. Pulled. You are pulled forward, down the hallway, to that ancient, blackened doorway. You reach out your hand to grasp the handle, feeling somehow dirtied by just touching it, but it strikes you how very clear of dust it is. The door swings open too easily for you, where yawning darkness waits…

If this overwrought paragraph of prose strikes you as oddly familiar, then you have read or watched something in the genre of gothic fiction. It developed in the 18th century as a combination of fiction, horror, and Romanticism that swept into a lurid style of storytelling. The Mysteries of Udopho in 1794 provided the inspiration for an entire school of writing which rapidly took off, to the point of pastiche and parody.

Out of the Castles and Into the Night

Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein predated the rise of true horror fiction and science fiction by a century, and it is impossible to deny their impact on literature as a whole. It was only in the 20th century that horror as a genre moved out of the dusky, damp castle and out on its own again, but gothic horror remained strong in its heritage.

As film and other media grew, so too did gothic horror. It adapted itself to the German expressionism of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and exploded into gruesome color with the many monster films of Hammer Studios. Today gothic horror retains a strong tradition, with its own lexicon of images and themes that are universal throughout its many forms.

Which brings us to the difficult problem of gothic horror tabletop gaming.

While there exists many games that have delved into gothic horror, the choice to run a gothic horror roleplaying game is daunting. As someone who genuinely enjoys the genre, even I find it difficult to run a good session of gothic horror. As such, I wish to discuss the matter of gothic horror RPGs, from the origins of gothic horror in the tabletop RPG format, through its odd successes over the years, to the current games on the market which feature gothic horror prominently. Finally, I will impart my own tricks of the trade that I have learned in running a good gothic horror game in the hopes that my success can be replicated.

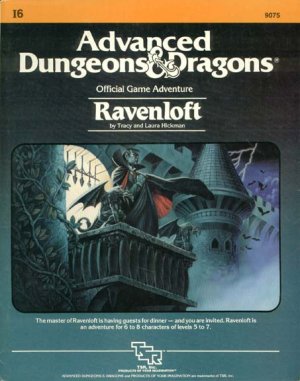

One cannot discuss gothic horror in tabletop roleplaying games without first addressing the original gothic horror module. I6: Ravenloft, written by Tracy and Laura Hickman, pitted a party of heroes in Advanced Dungeons and Dragons, circa 1983, against the dread vampire lord, Strahd von Zarovich. Brooding in his titular castle, Strahd pursues who he believes to be the reincarnation of his lost love, luring the PCs into Barovia to further his plot.

Ravenloft served as the launching point for the incorporation of horror elements into D&D and played to many of the themes and devices of gothic horror. The PCs were isolated, unable to leave the valley of Barovia until Strahd is defeated. Their resources are limited, and their own minds and bodies could be turned against them. As a vampire, Strahd was already an iconic monster of gothic horror, and his motivation of an unrequited love who killed herself rather than be with him was necessarily melodramatic.

Add in elements of a fortune reading to discern Strahd’s weaknesses and motivations, and top it off with a sprawling dungeon crawl through a decaying castle filled with danger at every turn, and you have a recipe for one of the best D&D modules ever written. Ravenloft was so successful it was followed by a sequel module, has been re-released twice, and inspired an entire setting for 2nd Edition D&D. It was also remade for D&D 3.5 Edition as Expedition to Castle Ravenloft in 2006.

This vast Ravenloft expansion allowed gothic horror to come into its own for D&D. Throughout the 90’s and into the early 2000’s, supplements were released for Ravenloft which contained nearly every theme and trope gothic horror had ever produced. There were dozens of tragic monsters, running the gambit of vampires, werewolves, demented alternate personalities, created humans, and everything in between. The monsters of Ravenloft were each compelling figures, weaving dark deeds with terrible results time and again.

Ravenloft itself was the ultimate setting of isolation and powerlessness, where the heroes could struggle eternally against the night, only to never truly be able to save the world. The world of Ravenloft itself was evil, and it fostered further evil in many horrible ways, punishing the wicked even as it rewarded them.

I came to Ravenloft in the 1990’s, following the villain Lord Soth from Dragonlance to its misty shores, and it is not an overstatement that Ravenloft is what made me a lifelong gamer. I would not be a gaming journalist today if it was not for the influences of Ravenloft.

However, Ravenloft’s success was not a commercial one. It had no shortage of diehard fans, though, with the Kargatane group of writers being the greatest example. They managed to keep Ravenloft alive after Wizards of the Coast shuttered the many gaming lines of TSR’s D&D, and stayed active when the brand went to White Wolf in 2001. Yet even with all their hard work, it eventually stopped production and has remained that way ever since. While there has always been a strong community supporting it, currently located at the Fraternity of Shadows website, Ravenloft as a game line ended in 2004 when the license reverted back to WotC. Elements of it were incorporated into D&D’s 4th Edition, but the game was ultimately dead in the water. Despite its critical acclaim and obvious creative interest, it is undeniable that Ravenloft proved a commercial failure across three companies, two and a half editions, and 15 years of print.

Ravenloft’s Influence

Ravenloft was not the only gothic horror game on the market in the 1990’s, however. Vampire: the Masquerade was very much a gothic horror game, as well as a game of the time. It featured monsters fighting a slow mental decline into madness, surrounded by ancient, unbeatable monsters which probably already were insane. Wraith: the Oblivion was also strongly gothic in its themes, and Vampire: Dark Ages drove the point home by setting it in the height of Gothic Europe.

Ravenloft was not the only gothic horror game on the market in the 1990’s, however. Vampire: the Masquerade was very much a gothic horror game, as well as a game of the time. It featured monsters fighting a slow mental decline into madness, surrounded by ancient, unbeatable monsters which probably already were insane. Wraith: the Oblivion was also strongly gothic in its themes, and Vampire: Dark Ages drove the point home by setting it in the height of Gothic Europe.

Kult was another horror game that emerged in the 1990’s, though it was far darker in many aspects than Ravenloft or Vampire and developed a very sinister reputation for its extremely mature themes. Call of Cthulhu also gained popularity in the 90’s, but like Lovecraft’s horror, it was more a deconstruction and rejection of the gothic setting than the embrace of it. Lovecraft’s horror was not one of ignorance and isolation, but knowledge and access. Of these three, only the Call of Cthulhu made it out of the early 2000’s still in print.

Luckily, there have been several games that have recently come to the market which gives hope to us fans of gothic horror. The French game Shadows of Esteren has been translated into English and is releasing its third supplement after several highly successful Kickstarting campaigns. Openly inspired by Ravenloft and Call of Cthulhu, Shadows of Esteren places the heroes in a world filled with nebulous, shadowy ancient threats of a natural origin, during a cultural conflict between three great powers.

Another excellent gothic horror game is Annalise, a wonderfully written independent game that allows for several players to work together to tell a story of gothic horror. Extremely aware of the themes and motifs of gothic horror, Annalise is the easiest game I have found to introduce players to gothic horror, and it is certainly a game you should be playing.

Finally, the Blood and Smoke update for Vampire: the Requiem has brought back the monstrous vampire who is inextricably linked to gothic horror, casting all kindred as supernatural, psychic nocturnal predators who are struggling against not only their own internal monster, but the incessant need to be a part of the mortal world to stave off maddening boredom.

I even have a great deal of hope for the chances of Ravenloft returning as a part of the next iteration of Dungeons and Dragons. While there have been no announcements yet as to that effect, the playtest material of the open beta features a game where the rules are streamlined, and the power curve is not nearly as drastic as the previous two editions. D&D Next plays like a perfected version of D&D’s 2nd Edition to me – and that makes it perfect for Ravenloft. When you add in WotC’s announced plans for modular releases as well it raises the possibility that Ravenloft may finally be returning to us.

Running a Horror Campaign

The root of Ravenloft and other comercial failures of gothic horror games lies with horror – especially gothic horror – being a challenging genre to run. Much of gothic horror’s appeal comes from a pleasing sense of fear and dread, enacted through the safe distance of fiction. It strips its protagonists of knowledge, power, and agency, holding them in the dark and threatening them with vague dangers. And yet, through this fear, the protagonists are drawn forward into a confrontation with the root of the horror, and are forever changed by it.

Tabletop games by contrast are generally games of empowerment and escapism, not powerlessness and examination. Horror games suffer as a result of this, and the challenges carry through to the tabletop itself. Horror is a unique challenge to run as a Game Master, but one that can be very rewarding.

To run a good horror game, the first step is having players who are interested in playing horror. That may seem a bit of a given, but it is still a very key point. Horror is not about overcoming monsters and saving the day despite being scared. Horror is about watching the destruction of something inextricably human and associating yourself with the destroyed. Gothic horror in particular is about a lack of power, watching a dwindling pool of options slowly peter out until you are left with only one terrible course of action.

Many of the trappings of gothic horror, such as the decaying castle, the fog-drenched moor, and the once-human monster, exist to bring attention to the destruction, and eliminate escape. Therefore, players must be not only willing to lose in a horror game, but they must be willing to accept that victory might have been impossible. Even when you win, you will still lose something precious. It’s imperative that players know this going into it.

Once you have the group of willing players, the next step is having a compelling story. It is important in gothic horror for your antagonist to be powerful, dangerous, and compelling. The players, if not the PCs, must be able to empathize with the villain. That said, the villain must also have some trait which makes them almost impossible to defeat and a motivation that is seemingly unforgivable.

Indeed, while redemption must appear to have been possible for the villain at one point, that point needs to be past.

Finally, you need a story that not only brings your PCs into conflict with the villain, but allows them to explore the world of the villain. Make it necessary that they learn about the villain in order to defeat them. Ignorance is the weakness in gothic horror, and it is only through knowledge that they can become powerful.

Moreover, when running as a gothic horror GM, be merciless. That is, don’t kill PCs arbitrarily, but do not pull punches. PCs must never truly feel safe, and let the players inform you how to do this. Find out what the PCs care about, and threaten that. Hurt the heroes in ways that do not heal, and put the pressure on them.

However, also let the heroes heal. Let them develop new relationships on the ruins of the old ones. Let them build themselves back up, so you can knock them back down again. Never award them a cheap victory, and they will grow to love victory for all the effort they had to put in. Most importantly, learn what the players themselves cannot handle in a game, and avoid it. This may be just a game, but trigger warnings exist. However, if something is not a trigger to the group, it is fair game. Be. Merciless.

With players on board for horror, a compelling villain, and merciless game mastering, you will have the root of a good gothic horror game. Fill out that framework with the trappings of gothic literature. Creepy castles, suspicious villagers, soothsaying ghosts, and mysterious destinies are all good.

While you’re at it, turn off the heat or AC. Open a window. Turn off the lights, and play by candlelight. (It helps.) Find ways to keep your players slightly ill at ease, as having your players uncomfortable helps immensely in setting the atmosphere.

Additionally, don’t forget to hit every sense that you can while describing things, and don’t be afraid to push certain lines. Always bring up details which are unnecessary but the sort people would fixate on.

Every little brick of information helps build the world of gothic horror, and you will need every last one to make the story a memorable one.

Gothic horror remains firmly entrenched in the world of fiction, and the interactive fiction of gaming is no different. Whether you approach it on the fog-drenched moor, or in the confines of a haunted office building, the themes of gothic horror’s isolation and powerlessness can strike anywhere. While running horror is never easy, it can be amazingly rewarding if done properly. Gothic horror is where modern horror sprang from, and it remains compelling even today. With a little bit of work, and a little bit of luck, you can overcome the difficulties of bringing those gothic horror tales to life off the page and on to the tabletop.

David Gordon is a regular contributor to the site. A storyteller by trade and avowed tabletop veteran, he can be reached at dave@cardboardrepublic.com.

You can discuss this article and more on our social media!

Photo Credits: Bram Stoker’s Dracula by Constable and Robinson Publishing; Ravenloft by Wizards of the Coast; Zoltar Machine by HauntedProps; Vampire the Masqerade by White Wolf Publishing; Nosferatu by Jofa-Atelier Berlin-Johannisthal; Dr. Claw from Inspector Gadget by DiC Home Entertainment; Willy Wonka by Paramount Pictures; South Park goth kids by South Park Studios.