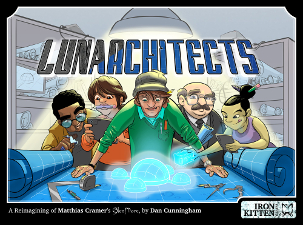

Back in November, Kickstarter saw the launch of Lunarchitects, a science-fiction themed tile-laying game by a first-time campaigner Dan Cunningham. We were also fortunate enough to preview the game. Just over a week ago, the campaign closed 10k above the desired funding level.

For the record, I’m glad Lunarchitects funded.

For the record, I’m glad Lunarchitects funded.

Normally this would hardly be newsworthy. Games successfully fund daily at this point. No, the issue at hand is that Lunarchitects became embroiled in another case of a public forum dispute that put a game’s future in jeopardy, in no small part because it peeled back a pair of hidden issues that exist just under the surface of the gaming world.

The Unofficial Gatekeepers

The first has to do with status. Gamers are a passionate group. We have to be. It’s a niche hobby compared to the world writ large, and so on some level most of us carry a tiny chip on our shoulder about that fact, though worn primarily as a badge of geeky pride. This allows us to fit in with other gamers and collectively share the joys (and frustrations) of gaming. Gamers are also an opinionated group, and there is no shortage of people willing to share those opinions. When those two factors converge, though, the result isn’t always positive.

Even for a niche community, gaming is hardly homogeneous in idea or makeup. This is perfectly fine. I firmly maintain that there truly is a game for everyone out there. There is a reason that Twilight Imperium and Cards Against Humanity are both beloved games even though they are vastly different and cater to wildly different types of gamers.

No, the problem is when others start trying to dictate why one style is superior to another, one disparate title superior to another, one gamer superior to another. And that’s bull.

You like light 20 minute family games? Go for it. Marathon 18xx games? All the power to you. Cube pushing, zombie slaying, minis painting, LCG-building, rail making, co-op fueling – it’s all good. ALL OF IT. At the end of the day, gaming should focus on the games themselves. Play the games that you like; the rest is immaterial.

However, when you start trying to stratify those types, or the people that like them, that’s where we get problems in the community. It’s the notion that Telestrations shouldn’t count the same as Battlestar Galactica or that Crokinole is a lesser use of one’s time than Food Chain Magnate. Have your preferences and channel those preferences into being passionate and opinionated about them. Just don’t do it at the expense of others because their tastes differ.

Case in point: the current struggle for the #1 spot on BGG. Personally, I could give two licks about BGG rankings. Still, for some it’s a very real thing with real implications. The fight between the grizzled long-standing strategy steward Twilight Struggle and the lighter more casual-friendly co-op Pandemic: Legacy isn’t solely about the games themselves. It’s about status, and it’s about shaping gaming’s identity. (In a lot of ways it’s unfair to even compare the two contenders since they’re wildly different play styles, but that’s another topic entirely.)

The same divisiveness comes when you start dealing with notions of exclusivity due to availability. While I disagree with the idea that ‘only bad games go out of print’, pointing people towards discontinued titles over re-implementations doesn’t help the greater whole either. These are the voices who espouse that you shouldn’t play Rex because Dune is superior, even if the latter requires the combined efforts of Ben Gates, Indiana Jones, and Lara Croft for the average gamer to locate.

Or, in the case of Lunarchitects, those who say that you should only play the out of print Glen More over this next-gen Kickstarter. Part of this is simply because Glen More is the older (and therefore somehow more reputable) game of choice. If that were the sole criteria, then no one would ever play any trick-taking game other than Karnöffel – using the 14th century rules of course.

No, part of the pushback is because it’s also a different designer…like almost all games. This wasn’t Midgard coming back as Blood Rage or Agricola morphing into Caverna. This was emulation and evolution at work. Gaming is an constantly changing medium, and new games come out all the time that resemble those before it. Lunarchitects just made the unfortunate mistake of using what most games designers do to some extent as a selling point.

I don’t claim that either game is superior or inferior to the other because, having played them both, I believe there is enough of a difference to merit both games’ existence. It’s why we agreed to do a preview of the game after seeing it, tucked away in the Double Exposure room amidst all of the fervor and excitement of Gen Con 2015’s massive expo hall. And it’s why we stand by that preview. For some, Lunarchitects is a better choice because it was available to get affordably over Glen More or because they prefer space themes over the Scottish highlands. Others may prefer the square tiles over hexes or the slightly simpler ruleset of Glen More. Both. Are. Valid. Denigrating supporters because they don’t want to pay more for an out of print game or because it was inspired by something that came before it is not. It just smacks of elitism.

To those who think it’s a carbon-copy ripoff of Glen More: play it first. Yes, Lunarchitects borrows heavily from its inspiration and bears more than a passive gameplay resemblance to it. The same way that practically every worker placement or deckbuilder does.

That fancy new Euro with rondel-style movement? Someone came up with the rondel first, which is directly based on action-taking mechanics, which in turn is directly based on the same non-linear gameplay philosophies of all modern games. That’s pretty much how design works, game or otherwise. People borrow, co-op, and steal ideas constantly. Every game that comes out today, from new mega hit to the latest dud, stands on the shoulders of the games that came before them. You can’t copyright an idea, nor would you want to. Magic: the Gathering pulled one of those off and it hampered card game design for two decades.

He Said He Said

The second issue that reared its head during this campaign happened at the crossroads of Industry and Hobby. It’s an intersection that we as gamers have a really hard time with. Games may be just games when they’re on your table, but until that point there’s a lot of actual work that goes into getting them made. This was highlighted during a BGG thread that had players discussing the moral and legal standing of this Game By Another Name, which, as usual, saw people break down into the same three camps.

First was a contingent of gamers predisposed to believe newcomer Dan Cunningham. They saw an unknown designer trying to do right by being honest on where the game’s foundations came from and who seemingly took all the right steps for transparency, only to have it bite him by the self-styled gaming establishment. Many of these defenders barely know the name of Matthias Kramer, and so his 11th-hour summons to the conversation did little. To them, this Kramer person offered conflicting statements about whether or not he gave his blessing, and it only spurred the pro-Lunarchitects people into final drive action to avoid the campaign being torpedoed.

The other side consisted of a group of people who ranged from confused to irate about the whole concept. They didn’t even have to play the game to know that this upstart was trying to profit off of a well-received game by a well-known German designer. Glen More’s sacrosanct place in the gaming pantheon should not be challenged. It didn’t matter that an English version of Glen More has been out of print for years – you could still get it if you wanted the real game. This Kickstarter was clearly a clone, and how dare this new designer challenge the word of Matthias Kramer? It’s Matthias-freaking-Kramer. Why should anyone believe claims to the contrary from the guy the whole game is predicated on?

Fun!

I largely avoided the whole topic, partly because we preview games solely on the merits of the game itself; anything outside of that isn’t our focus. Generally though, as part of the third and final group, I avoid wading into the business side of game development disputes. Many often forget: gaming may be a phenomenal hobby, but it’s still a business. Companies still need to sell their games to keep making more games, and like any business environment, disputes happen. These sorts of arguments happen regularly.

Really.

We as the general public just rarely hear about them unless something goes askew for one reason or another and someone takes things public. Take the recent Martin Wallace / Brass fiasco earlier this year. Even with the limited amount of information released it was clearly a long-standing issue between the two parties involved. Some immediately took to supporting the veteran designer’s claims, some the established publisher. Yet most people – wisely I might add – opted to stay out of it entirely. Unless it’s egregious and clearly one-sided (which happens less than you’d think), it’s usually best for us consumers and enthusiasts to tread lightly on making snap decisions on legitimacy over behind the scenes matters.

To that end, I’m glad that Lunarchitects exists. I’m just not highly enthused that what started off as an homage project turned into a series of incidents exposing that the gaming community is once again more segmented and stratified than we’d like to believe. There seems to be a lot of that going around these days. It’s possible that it could be yet another facet of the growing pains and kickback from people clinging to the status quo fearing change, but if not, then it means we still have a ways to go to ensure that we treat all games – and gamers – with equal standing.

We’re small enough of a community that we don’t need more elitism: we need more egalitarianism. That doesn’t mean we all have to like the same games or styles, but we should at least all be on board with encouraging people to enjoy what they want to without needless and divisive caste systems as a means of gatekeeping the hobby. Here’s hoping we all work on that in 2016.