Author’s Note: When I started writing Extra Pieces, I wasn’t really sure where it would go, but I wanted a heading to encompass all those extra bits of gaming that are neither reviews nor playing guides. If you’ve been reading for awhile, you’ve seen that it’s a little random, and overall I think that’s a good thing. Still, I like structure, and I’d like to add a bit more to this section of the site.

That said, this is the first in a new series of posts on how we use to games to tell stories, to create myths, and to give meaning to our own narratives. Series, though, is perhaps the wrong word, as it implies a continued, uninterrupted string of articles, and that’s not what I intend here (at least not for the moment). I’ll be bringing you these articles as I write them, as they occur to me, hopefully about once a month.

As always, though, I value your feedback. If you want to read more – or less – of something, please let me know!

Now, onto the important(ish) bit:

Narrative Gameplay: The Isle of Doctor Necreaux

I was tempted to choose a more traditional game as the launching point for this new series, but The Isle of Doctor Necreaux kept coming back to me. It isn’t particularly well-known, nor is it well-loved (it has a rating of 5.7 out of 10 on BGG), but despite its flaws, it plays with theme, pacing and character in an evocative way. It’s not a story-telling game like Once Upon a Time, nor is it as complex a world-building engine as Arkham Horror, but it sets up a simple and clever system through which players can guide the narrative.

The Isle of Doctor Necreaux presents you with a story arc, and it’s one you’re going to be familiar with if you’ve ever seen a 1960s spy movie (or Austin Powers). Evil Dr. N. has kidnapped a team of scientists and forced them to build a doomsday device deep within the labyrinthine tunnels of his “secret” volcano lair. He will set off the device in four hours unless all the world leaders agree to submit to his will. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t get many takers. In fact, the world governments assembled a crack team of agents to infiltrate his lair and plant a bomb. It will go off long before Dr. N.’s doomsday device, effectively saving the world.

The Isle of Doctor Necreaux presents you with a story arc, and it’s one you’re going to be familiar with if you’ve ever seen a 1960s spy movie (or Austin Powers). Evil Dr. N. has kidnapped a team of scientists and forced them to build a doomsday device deep within the labyrinthine tunnels of his “secret” volcano lair. He will set off the device in four hours unless all the world leaders agree to submit to his will. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t get many takers. In fact, the world governments assembled a crack team of agents to infiltrate his lair and plant a bomb. It will go off long before Dr. N.’s doomsday device, effectively saving the world.

And that’s where the game begins.

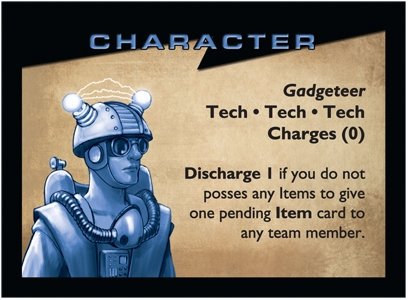

Each player is an agent on what is effectively the B Squad. The bomb is already planted and the world is already saved, and now it’s up to the players to rescue the scientists before the detonation. Gameplay is cooperative, though there is some potential for betrayal. Each player is technically one character, but each character is composed of three distinct, semi-random character traits with unique bonuses, such as Robust (reduce damage) or Security Expert (defense against traps). These traits are dealt out in what I now call “7 Wonders Style” – each player is given three. They select one, then pass the remaining two, and so on.

This character creation balances control and randomness so that players can build characters they’re actually interested in, but they’re not able to min-max. A tech-focused character could ultimately end up with a combat trait as well depending on what the players ahead chose to pass on. Of course, there’s no story inherently present in this mechanic, but it leaves ample space for character and narrative should the players choose.

This character creation balances control and randomness so that players can build characters they’re actually interested in, but they’re not able to min-max. A tech-focused character could ultimately end up with a combat trait as well depending on what the players ahead chose to pass on. Of course, there’s no story inherently present in this mechanic, but it leaves ample space for character and narrative should the players choose.

Each turn, players have the choice to rest and regain health or to forge ahead through the tunnels of the lair. Should players choose to act, they must then decide how many Adventure Cards they will draw that turn. Adventure Cards are essentially encounters. The deck contains items, villains/minions, traps, rooms, and events. The Scientists card is shuffled into the middle third of the deck, and the Escape Shuttle is shuffled into the last third. This ensures somewhat consistent play time, but it also pins down the central aspects of the story arc even as the actual pacing of the story is left in the hands of the players.

Of course, the decision of how many is a strategic one. Do we draw one Adventure Card and know that we’ll probably survive, but that we won’t make much progress? Or do we draw ten Adventure Cards, risking our lives but facing much better odds of drawing the card we need? But it also determines the narrative. Is this the story of the team of seasoned professionals who pace themselves? How desperate is your team? The speed with which players draw determines the speed at which the narrative unfolds.

And, unsurprisingly, players always end up drawing more cards as the Adventure Deck depletes. This imparts a sense of urgency – the clock is ticking down, the bomb is about to go off, and you don’t know where the shuttle is. There isn’t time to rest. This is the game’s equivalent of the chase scene, and the pace is frantic. The end is within reach, and it’s hard not to push your luck – just one more card, just one more. Maybe it’s the shuttle? Maybe you’ll make it out alive.

Or, at least, some of you will. Through trap doors and nefarious plots, players can get separated from the pack, and if one group reaches the shuttle before reuniting, those players have the choice to leave immediately, effectively condemning their teammates to death.

Or, at least, some of you will. Through trap doors and nefarious plots, players can get separated from the pack, and if one group reaches the shuttle before reuniting, those players have the choice to leave immediately, effectively condemning their teammates to death.

Sometimes, this can serve the greater good. If the team with the shuttle also has the scientists and time is running out . . . well, some sacrifices have to be made. Other times, players can choose to leave without the scientists, effectively failing at their mission but saving their own lives.

This choice has interesting narrative consequences and though the story arc is essentially identical from one playthrough to another, the overall game can have a very different feel depending on which ending was chosen. Regardless of the players’ choices, each game ends with the bomb detonating and the world being saved, but the story of the characters – whether they are heroes, cowards, unlucky bastards, or just barely good enough – varies substantially from between sessions. The rulebook spells out several possible endgame scenarios, one even involving Dr. Necreaux escaping at the last moment, depending on the choices of the players.

Of course, when you’re playing, it doesn’t necessarily feel like a choice. If one player is separated from the rest, and the main group finds the scientists and the escape shuttle . . . well, is that really a choice?

Technically, yes. It’s not a particularly good choice, but players have the freedom to wait, to give it one more turn, to hope that their friend can rejoin the pack. And this is the key to the narrative decisions in The Isle of Doctor Necreaux: the choices are not complex, but they tell a powerful story.

The game plays with cliche and classic spy movie tropes to create a fiction that’s compelling, even if it’s not particularly novel. And the choices players make, even the relatively minor ones, have large impacts on the overall narrative as it unfolds. Though it did not set out to be a story game per se, The Isle of Doctor Necreaux provides a strong narrative arc upon which players can construct their own stories of personal success and failure.

![]()

Erin Ryan is a regular contributor to the site. Feel free to share your thoughts over on our forums!