As part of our November Spotlight on Dice Hospital, we strive to inform readers of little extra tidbits surrounding the game. Games are made by people, and one of those tidbits we enjoy is learning a little bit more about the people behind them. Some designers shy away from the public stage, while others enjoy being front and center.

For Stan Kordonskiy, co-designer of Dice Hospital, he is more than happy to talk about his inaugural board game title. In a desire to reflect his real world profession, Stan started dabbling with game design merely as an exercise in seeing if there would be interest in a game based around what he does for a living. As it turned out, there was. This has resulted not only in the initial success of this game, which bears significant meaning to him, but it has also catapulted him into several more designs which are also pending.

The road he has taken as a designer has been one of enlightenment and frustration – as it often is for first-timers. Still, he has seemingly taken these lessons to heart and learned from them, while never deviating from the reason he took up designing in the first place: to create something he feels others will enjoy and to help give back to a hobby he enjoys so much.

The road he has taken as a designer has been one of enlightenment and frustration – as it often is for first-timers. Still, he has seemingly taken these lessons to heart and learned from them, while never deviating from the reason he took up designing in the first place: to create something he feels others will enjoy and to help give back to a hobby he enjoys so much.

Which, when you consider the fact that his primary activities are as a caregiver for the ill, means that he must really like us.

Despite Stan’s busy schedule, we managed to carve out a significant chunk of time to chat. In this piece, which is part interview and part design journal, we cover the inspiration for making Dice Hospital, his evolution as a designer, the game’s evolution from his original design, and his hopes for future efforts. This interview is a tad longer than normal, but it’s well worth the read. So let’s get right to it.

Enjoy!

CR: So, let’s start with what caught our attention most: how did you come up with the theme of Dice Hospital?

I’m actually a registered nurse by trade; I’ve worked in the emergency department for the past eleven years all over the country. I’m also a board game enthusiast. I wanted to create a game that would be basically an emergency department game, so I designed this game called Stat!, with patients coming in and getting discharged from the ER – basically my job. I made it into a prototype which I put on The Game Crafter, paying a little money for some basic art work to have a finished game. Just as an exercise in game design partially and hoping to gauge interest in doing something like a Kickstarter down the road.

Not long afterwards all of a sudden I get like a message in my email saying they were a publisher were interested in this game. At first I thought somebody was playing a joke on me or, because it was coming from out of country, I thought maybe someone was trying to maybe scam me. I was like, ‘Who is this guy trying to contact me from this company I’d never heard of?’ But I did a little bit of research and started messaging them back cautiously, and we started talking. And that’s basically how I met Caezar [Al-Jassar, of Alley Cat Games].

At the time I think Caezar only had one game published, Lab Wars, so here we were, me a first time designer and he close to first time publisher. So we kind of hooked up over this project. From there it got changed into a hospital setting instead of just an ER to incorporate more stuff, and he brought in Mike Nudd, who I knew because of a Waggle Dance review, to the project because he wanted to make some changes. While we were making changes, he and Mike did the same, albeit they could do those things a little easier being face to face in UK.

What ended up happening is that we a kind of development completely independent of each other, where I was designing stuff here, he was designing stuff there, and that turned into the game that Dice Hospital ended up being.

CR: Was it difficult at all as your first game kind working with somebody a couple thousand miles away and revising your very first game?

It taught me that you have to be able to hand over the reins to your game. It’s a thing that you hear about from other accomplished designers but don’t really internalize it at first. You think you’ll be still involved every step of the way, but you really can’t be. The publishers have the final say in these matters and the best you can do is just help out and try to steer them sometimes if it’s something that you feel is really important to the design. At the end of the day, if you want 100% control over the game you have to publish it yourself, and even then you will have to respond to manufacturers’ demands, to backers’ demands, to a million different things that control a publisher’s perspective and pressures them to change the game in a certain way. It was a good lesson. I’m totally cool with it now, but it was a little difficult for me with Dice Hospital because, like you said, it was my first project.

CR: The game was picked up by Alley Cat and brought to Kickstarter. Had you ever been involved in any sort of Kickstarter project before?

I think I backed a game prior to that! I was familiar with Kickstarter as a consumer but not in any kind of project or anything. I still don’t know that much about it compared to a lot of other people. I know tons more than I knew before, but I don’t think I could do a Kickstarter project right now by myself. But I was excited to see my game go on Kickstarter and get funded so well.

CR: What did you feel when you were watching the reception to the game?

I felt extremely lucky. I look at Kickstarters all the time, and sometimes the ones that I think should do well don’t do well at all. You never really know 100% what’s going to happen. So that morning, when I saw how many backers we already had right after launch, I was like, ‘Oh my god this is wonderful!’ I was just hoping for this game to fund so it could get published. And it looked early on like it was going to a real success. It was definitely a huge milestone…knowing it was succeeding so well was a huge relief.

I also felt vindicated in a way because I’ve been told by a publisher or two that it was a bad theme, that it’s not as good as more ubiquitous themes, that there was a very small market for things like fire-fighting games or hospital games or more ‘fringe’ ideas. My whole idea was that this is something where everybody has a connection. Sooner or later, everybody can relate to the whole hospital experience in some way, so why couldn’t it be very universal thing that everybody would want to experience?

Because of that, I started doubting in the back of my mind that maybe gamers wouldn’t want to do a job so to speak, that they only want to play out fantasies. So it was great that I was right. I was thinking about it from a psychological standpoint and what would make people want to play a game beyond just the plastic and the dice. I felt like I connected with people and that I guessed correctly.

CR: You mentioned that it originally focused on the ER and then broadened into hospital care in general. Did that change a lot of the underlying mechanics at all, or was the basic function of the game still the same?

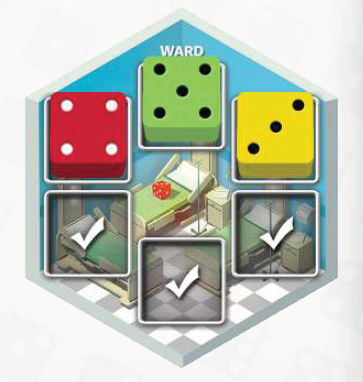

No, it didn’t change a lot of mechanics. The central idea was that dice were patients and pips were health. Workers go and try to increase that health, and if they don’t the health drops. A lot of things did get changed, but it was just more minor mechanical things. At first I was putting dice directly into the rooms, where the worker would then go in. If a patient would be with a nurse in the room at the end of the round then the dice wouldn’t deteriorate, but if they weren’t then the die drops. It was just a slightly different flow. I also had these specialists in the game and your hospital was kind of pre-set, but for the specialists you acquired.

What Caezar did was add rooms. He wanted the hospital to grow as you played and so it just made more sense that it would be a full hospital because there’s only so many areas you can add to the emergency department. Plus I think being in the UK health system it’s slightly different how they do the ER, where here in the US it’s kind of a catch-all from a sore throat to a major injury. In the end it made more sense for it to be just a hospital where anybody could be treated. There were a few other changes too, but the biggest one was that they wanted the rooms to be drafted. And you could get the specialists originally that would give you different special abilities.

Nevertheless, Caezar always liked the health care angle of this game. He’s into science and likes making science themed games, so I think we were of the same mind.

CR: What was the catalyst to take your day job and turn that into a game?

I wanted to give people a taste of the flow of my job because a lot of it is time and resource management. At work I always feel like you have these 3-4 situations and you have to decide which situations you’re going to attend to first. If you can’t attend every situation, which one do you not attend to at all?

It’s a weird thing that people don’t really get a sense of portrayal of these jobs – they always think these people are super human and can do everything like on TV dramas. In real life it’s a lot more like a puzzle-y job. What should I do first? What affects my decisions? How do you do things in such succession that it’s most efficient? Which is something that board gamers can understand.

It’s funny: people enjoy this game who obviously have no connection to healthcare, but when I play this game with people who are hospital workers – doctors, nurses, etc. – they often remark how this feels very much like their job. You’re just trying to make these decisions and you’re trying to do your best. That was the whole point, to convert my routine into game form. And I already had a lot of background knowledge, so it was a lot easier to come up with names of equipment and specialists which helped to get the game wrapped up in this theme without having to do a lot of research like I’ve had to do on my other games.

CR: How did you come up with the idea for using dice as patients?

I don’t remember exactly. I just thought it was kind of an obvious move. I play a lot of dice placement games like Alien Frontiers and Kingsburg, and I liked that there’s really not a bad die in the game. I wondered how to represent that in my game. I thought maybe the sick dice may be worth more points and the healthy dice aren’t worth as much but are easier to get rid of, so you have that choice to balance it out. In the game that’s represented by values going up and down.

It is abstracted versus a meeple on some kind of track, but I don’t like fiddly games. My personal favorites are when games wrap things up in an elegant, easy to do package; I don’t like games that have tons of tracks and tons of things to remember. I didn’t want to do anything like that. Here the die goes up, the die goes down. If it goes past six it gets discharged; if it goes past one it goes into the morgue. That part I kind of already had in my head, and I just kind of built a game around that to a certain extent mechanically, where there are no bad dice. All the dice are valuable in some way.

CR: Were there any parts of the game that were removed that you kind of wish had stayed, or anything that they wanted to add in that you personally decided you didn’t to have?

I don’t think there’s anything in the game that I don’t want to be there. I don’t think it’s all needed necessarily for every player, but some of it is for people who want a more complex experience. I think the base game works really well as kind of like a light to light-mid Euro game and then you can build on that.

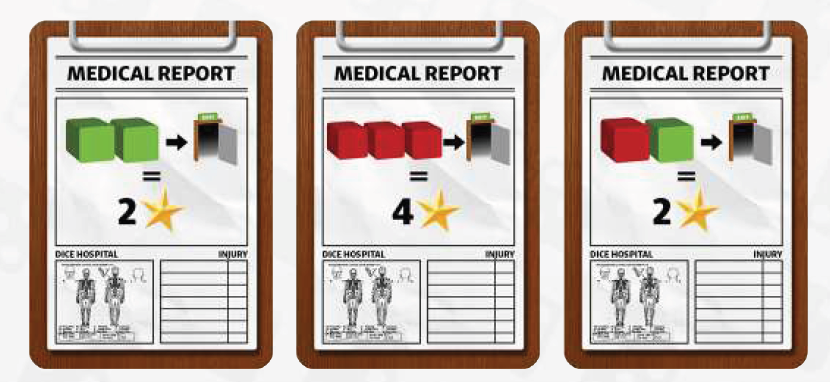

As far as what did make it to the game that was partially removed, there was one thing. The solo mode has these cards which have goals that you want to accomplish and you get some points. I once had this for all players, and when you discharged your dice you could claim one of them. It was another way to score points, but in my original design those cards also had a little power which allowed people to either get a bonus for themselves or to mess with other players. It made the game more interactive, which does address the one criticism I’ve heard leveled at this game is that outside of drafting you don’t really interact with other people, you’re just kind of doing your own thing.

There were different drawbacks to it though. It wasn’t a perfect thing, so I understand why it didn’t make it into the game. I don’t think that the game was worse for it, but there is a price to pay. With those cards you can’t really do things simultaneously, which slows things down, and there’s a lot of balance that needed to be done to ensure no dominant strategy emerged. I’m not saying it had to be there 100%, but it did exist and I liked that part. I personally would still maybe even play the game and just have those solo cards out as an option people can claim it if they discharged the right dice.

CR: What was the hardest thing to balance when you were designing and developing Dice Hospital?

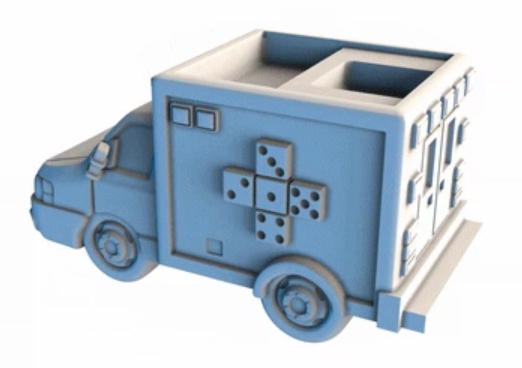

I went through several versions of the draft before we settled on the ambulances. I initially had it such that you just pulled dice from the bag and then you distributed them when you were the first player, so each player got a chance to do that. Which made it such that you were trying to screw other people a little bit by giving them the dice they probably didn’t want, but you also to think. The low dice were more valuable in my original version so you couldn’t just give everybody all the low dice to mess with them.

I tried several other things before eventually hitting on the ambulances well into development and Caezar really liked them. That’s where the re-rolling rule comes in, because we figured with ones and sixes that it’s just way too far on that continuum where it gets too good or too bad. We went through a lot of different ways before setting on this.

Of course, we then had to balance the numbers, because originally as I mentioned the lower numbered dice were simply worth more points, and the dice values were color-coded so it was easier to track. In order to make the game more accessible, they wanted them all to be random, so that took a little while to get right. We then created the blood bags as a reward for taking the low number ambulance and it ended up working out really well.

CR: What are some of your favorite dice placement games?

I actually do have a favorite, which is not easy for most genres. But it’s definitely Euphoria. I like Euphoria for the same reason I people like Dice Hospital: because while Kingsburg and Alien Frontiers are great, in Euphoria the pips represent the intelligence of your workers and then when your workers get too smart they rebel and basically skip town on you.

That touch to the dice placement game I find just delightful. I love explaining the game to people the concept that, yeah, you want the high numbers a lot but it also means that if they get really high and there’s a bunch congregating in the same area, they kind of conspire against you. That’s great. It is my hands-down favorite. Other mechanisms in the game are good too, but the part that the die represents something beyond its value is enjoyable – and intuitive.

CR: What would you as a designer like to see as the biggest impact this game has?

I think my wish for this game is that it has staying power. There’s so many games coming out now that many people don’t play a game more than once…I hope that the weight and theme of it and the connection that it makes to people will make it a more a perennial game like Stone Age became for a lot of people, that people will pull it off their shelf and play on a somewhat common basis.

That would be the biggest success to me, that it isn’t something that people are fired up about in the moment, talking about how they love the plastic ambulances and they love the novelty of it and then it just goes on the back of their shelf and they never play it again. I hope that the mechanics of the game is something that people are going want to bring to the table and play. Hopefully the lightness will actually work in its favor in that respect, where people aren’t going to be intimidated to teach or by the time it takes to play.

If I knew that even like five years from now people would still ‘oh yeah, Dice Hospital, sure I’ll play that’, that would make me happy.

CR: What evolved for you as a designer as you got further and further into making different games?

I understand how the business works much better, all the little things that the publishers have to deal with. From a game design standpoint I also started paying more attention to the psychology of it and not just concentrating only on mechanics, trying to understand why people play games not just how they play them.

I’ve also become more interested in storytelling aspects of a game. Not necessarily a complex thing like an RPG, but more of like, ‘what does this game say?’, because I started to realize that the reason a lot of people like a game is because it says something – even if they don’t necessarily realize while playing it. Something like Holding On is very forward in what it’s saying, but most games are more subtle than that. I try to make sure I actually know what my game says to the player when I start designing it instead of just being an afterthought, which I think in the beginning was the case.

I’m very much interested in in why certain things succeed and fail in the board game world, and I think that has a lot to do with that with the psychology of board gaming.

CR: Finally, now four games in (with more on the way), what is the designer experience for you now versus when you were making Dice Hospital?

It’s kind of a mixed bag. On the one hand I’m more relaxed about it because I know what to expect. I expect that I’ll have to give up control at a certain point, I expect compromises, I expect delays, I expect debate. On the other hand, I feel more pressure because now you’re sort of known somewhat and so you want to make sure you don’t fall on your face or become the kind of person that succeeded accidentally and now you can’t repeat your success. You just kind of want to keep doing well once you started doing well and you want to grow as well; you don’t want to stay on the same level.

At first it’s just not something you think about; you don’t really think about being one of the one of the designers people would mention by name because you’re just making one game. The more successful you get at it, though, you start to wonder if you can actually be a person that people would mention the way they mention famous designers. So it’s pressure you put on yourself to a certain extent, but I think it’s inevitable too. How can you not start thinking that way [after getting some success]? It’s definitely a mixed bag, it’s a lot of ups and downs and in design – ‘yes they signed it!’, ‘oh, I didn’t fund as well as I hoped’, ‘yeah this critic loved it!’, ‘oh this guy hated it’. It’s always a roller coaster. The only straight line is if you just get flat-out rejected.

Once it gets picked up it’s always like you’re elated one minute and then you’re disappointed the next. It’s very back and forth, and you just try to remember remember to take it one thing at a time.

Dice Hospital is a lightweight dice placement game where the dice themselves are the patients in need of your gracious care. Over the course of the game, new dice will show up in need of assistance, and your goal, naturally, is to restore them to their full D6 stature. With the help of some careful management, a couple specialists, and an oath to do no harm, it’s up to you to ensure that your hospital is the most efficient in the city at providing the best medical care possible. Those dice are counting on you because, well, they can’t count themselves.

To aid you in this altruistic endeavor, we thought it would be good to raffle off a day on the job at your local hospital, where you would be able to shadow real workers and get a feel for the challenges and triumphs of their noble profession. But after the fourth hospital told us to “stop calling”, we decided it’d probably be easier in the long run to go with a copy of the game itself for training purposes instead:

Photo Credits: Dice Hopsital cover and photos by Alley Cat Games.