Return with me, if you will, to the war-torn fields of Europe as they were during the Napoleonic Wars. Ignore those BBC reenactments that portray a brutal struggle in harsh elements, oppressive sergeants, incompetent or selfish officers, poor camp conditions, and bad food. There were no cannonballs screaming overhead, no clouds of musket smoke choking your throat and obscuring any hint of your enemy from view. There were no battlefield amputations, debilitating injuries, mad rushes, or covert operations…

No, the Napoleonic Wars were a refined, civilized affair. Armies lined up in rows opposite one other concealed under dark cloaks, obfuscating any chance of being seen from afar. It’s also possible they fought entirely at night, to better disguise themselves. Rather than pouring volleys of musket fire into advancing columns, soldiers (usually officers) approached enemy lines on foot. After singling out the nearest enemy combatant, he would calmly walk up, take off his cloak, and reveal his rank. His opponent would do the same. Whoever held the lower rank was honor-bound to consider himself captured, and immediately left the field.

I imagine the conversation went something like this:

“Good evening! Terribly sorry, I just tripped over that tussock there…”

“I say! Are you all right, old chap?

“Quite, thank you! But where are my manners? If I may introduce myself, I am Lieutenant Charmier. May I ask your name and rank, please?

“Jolly good to meet you! You have the honor of addressing Colonel Mayweather of his Brittanic Majesty’s 5th Light Infantry. So sorry, but it seems you are now in my custody.

“That’s quite alright, sir. I understand; there is a war on after all. Shall I just see myself behind the lines then?

“Yes, yes, that would do splendidly! Be sure to talk to Peterson by the Officer’s Mess. He’ll see that you’re properly accommodated until the battle is over. Shall I have the pleasure of your company at dinner tonight? I hear we should be having roast pheasant.

“That would be delightful! I’ve always been partial to pheasant, thank you!”

We Should Be Done In Time For Tea

This is not to say that war was without its dangers. Both sides adopted the tactic of covering piles of Bombs in the same cloaks, leading unsuspecting soldiers to reveal themselves to a pile of inanimate metal. Oh, they didn’t go off though – that would be uncivilized. If they exploded, how could they lure in any more officers? No, common practice was to have some NCOs jump out of hiding to point and laugh, then escort the fooled combatant safely off the field. The battle was considered won if one side captured the enemy’s colors, being a standard or flag often blessed by the hand of Napoleon/ the Brittanic Majesty themselves. To protect their quarry, they too were disguised under a heavy cloak and hidden among the rank and file.

As the Generals and Marshals themselves took to the field as high ranking officers, battles were instead run by advisors (sometimes called “players”), observing from a vantage point above the battlefield, such as on a convenient hill, bluff, or hot air balloon.

While this vantage point did not allow them to identify specifics about the enemy troops – likely due to the practice of using cloaks – it did allow them to direct single officers at a time. In the interest of fairness, when one advisor issued an order, they waited until their enemy counterpart issued an order of their own before directing another piece to advance.

Battles were fought between detachments of precisely 33 men, each of these small, brave groups consisting of no less than one Marshall, one General, two Colonels, and three Majors, with assorted lower ranking officers making up the rest of the army. Each detachment were also permitted precisely 6 Bombs and their colors, which was common practice at the time. There seems to be some confusion as to these ranks, however, as some questionable source materials claim that Colonels were typically placed in charge of regiments consisting of 1,000 men, with Generals and Marshals commanding multiple groups of said regiments. This is laughably absurd, as anyone engaged in a tactical simulations (commonly referred to as war / strategy games) could attest that keeping track of that many units is a logistical nightmare. The length of these battles would be impractical if thousands of soldiers had to take turns introducing themselves to their opponents. Clearly, such specious arguments fall apart at the slightest application of critical thought.

Proper Battlefield Practices

The commonly accepted rules of war stipulated that only the lowest ranking officers, Scouts, could advance at any speed greater than a dignified walk, allowing them to cross terrain much faster than their more esteemed comrades. It is debatable whether this was due to a casual disregard for a Scout’s social stature (being prevalent during these times), or that proceeding at a quickened pace would have winded the higher officers, preventing them from holding conversation with their enemies in a reputable manner.

In response to fears of high ranking officers gaining too much power in their positions of authority over 32 men, both governments commissioned the limited use of Spies. Perceived as civilian participants in a matter of high honor, Spies were considered contemptible by officers in the field and could be captured by a soldier of any rank. Historical records are unclear exactly what kind of blackmail these Spies were entrusted with, but if one was able to confront a Marshal on the field, the Marshal was forced to surrender himself rather than let some embarrassing secret be revealed.

The introduction of cloaked Bombs led to the adoption of Miners in most armies, who could identify the Bombs at close range and threaten to dismantle them unless the NCOs removed them from the battlefield.

If two officers met and found themselves evenly matched, both excused themselves from the field, having given pledges of safe conduct to one another.

Protecting the Quarry

Common tactics seemed to involve hiding an army’s colors behind a wall of concealed Bombs, with high ranking officers stationed in the area to intercept any Miners seen approaching the defensive line. As military intelligence services on both sides marked the spread of this strategy, some adopted a counter-strategy of bluffing, grouping the Bombs together but concealing the Flag in a mass of troops on the other side of the battlefield.

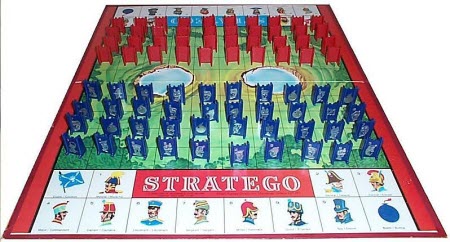

Sadly, this era could not last forever, and eventually the war petered out. Historians aren’t completely certain who won, enamored as they are with reenacting those battles themselves in their living rooms and teaching their children to do the same. Understandably, the lure of participating in this bygone era has caused use of tactical simulations of these conflicts, commonly seen under the commercial name ‘Stratego’. Efforts of Stratego’s attention to detail have ensured it remains an enduringly popular family game, whetting young peoples’ appetites for military history and setting an example for generations to come. Those with a mind for tactics and memory particularly find these enjoyable, and socializers as well will enjoy reliving the bluffing and intrigue that so defined this period of history.

Editor’s Note: Nathan Crocco has no understanding of history or international politics. His study of military strategy consists of extrapolating tactics from the backgrounds of old Far Side cartoons. Any statements and conclusions in this article should not be regarded as remotely accurate, nor do they reflect the usual standards this website demands.

The Cardboard Republic is not responsible for any views or misinformation presented herein, as they reflect the mindset of this individual reviewer and not the rest of the writers, editorial staff, or hosting site. He has been informed that this is an affront to any established academic study, and the editors are aware that many of the statements are inferred conclusions from sources that included The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy’s entry on Human Battle Tactics and old Blackadder reruns dubbed into Hungarian. The editors are also aware Nathan Crocco does not know Hungarian. Nathan Crocco admits to nothing.

Photo Credits: Starke by Livejournal; Napoleonic Battle by Gamewallpapers; Simmerson by Screened; Stratego board by Coolest-Toys.