Cover Stories: A Home With A View

I am not a fan of the Pathfinder RPG.

That is not to say that is not a good game. Quite the opposite: it’s an excellent game. It has a solid engine, widespread appeal, and does what it does well. It is, beyond a doubt, a very successful game as a result of these facts (and due to a very well-timed choice of when it entered the market). Pathfinder is an exceptional game in many ways, and one that has earned its name as one of the most recognizable brands in the tabletop RPG world.

Still, I am not a fan of the Pathfinder RPG.

I have played a Pathfinder campaign on three separate occasions, at three different power levels, and with three different Game Masters. I made certain to give the game a solid try each time, to play it as sincerely as I should. I wanted to like Pathfinder, I truly did, but the same familiarity that drew me to Dungeons and Dragons just turned me away from it. Every roll of the dice, every tally of situational modifiers, every choice of Feats and Skills – it all just brought me back to the dying days of D&D 3.5 Edition.

This was where Celerity, followed by Divine Metamagic: Persistent Timestops would be interrupted by a magical ring which could rewind the last 3 rounds of combat; where players had to create structured flowcharts to figure out their direct bonus to attack and damage would be; where Charging Smite – Leap Attack – Power Attack moves could explode into hundreds of HP in damage at the drop of an Initiative roll. Even with every step that Pathfinder took away from those days of “Cleric, Druid, Wizard, or GTFO, newb”, it still reminded me of the endless series of splatbooks and loot guides filling the shelves of my local gaming store and the thumb drives of my friends.

I wanted to like the Pathfinder RPG…but I couldn’t.

Which is why it is so very strange how much of a fan I am of the Starfinder RPG.

The Litmus Test

Those who have followed some of my previous works know that good science fiction RPGs is something I am always on the look out for and something I have a critical eye towards. (See: The Trouble With Science Fiction and RPGs) What you may not know is my own history with the space opera sub-genre of science fiction.

Those who have followed some of my previous works know that good science fiction RPGs is something I am always on the look out for and something I have a critical eye towards. (See: The Trouble With Science Fiction and RPGs) What you may not know is my own history with the space opera sub-genre of science fiction.

My recollection of adolescence is framed in the names of the authors I read, voraciously consuming the fiction of Anne McCaffrey and Andre Norton, Isaac Asimov and Frank Herbert, Arthur C. Clarke and David Weber. Before I discovered H.P. Lovecraft and Stephen King, the vast vistas of space and the high drama of its stories had taken root in my imagination. Watching Star Trek – both the Original Series and The Next Generation – connected me with my family, and I held the old VHS tapes of Babylon 5 that my aunt would record off the TV in New York as the greatest of Christmas gifts. In many ways, space opera is an old, dear love of mine, for both good and ill. When done right, I love it with an ardor and passion. Anything shy of that, however, and I will be a harsh judge.

As a roleplayer, both the old Alternity game published by TSR in 1998 and the d20 Future expansion for d20 Modern in 2004 were standout pieces in a genre which otherwise left me feeling neglected. Even these two games, however, seemed to lack that last piece of the puzzle to make me a True Fan, some element I just could not put to words. I quite enjoyed Eclipse Phase and even more “out there” games like The Void and CthulhuTech, but something just kept me from being satisfied with what I was presented.

As a roleplayer, both the old Alternity game published by TSR in 1998 and the d20 Future expansion for d20 Modern in 2004 were standout pieces in a genre which otherwise left me feeling neglected. Even these two games, however, seemed to lack that last piece of the puzzle to make me a True Fan, some element I just could not put to words. I quite enjoyed Eclipse Phase and even more “out there” games like The Void and CthulhuTech, but something just kept me from being satisfied with what I was presented.

It honestly was not until the Starfinder RPG came along in 2018 that I figured out exactly what it was the others were missing.

A Fine Launch Point

The Starfinder RPG is a tabletop roleplaying game by Paizo Publishing which presents a science fiction / fantasy universe set firmly in the sub-genre of space opera. Taking place ostensibly thousands of years after the Pathfinder RPG, players in Starfinder are adventuring heroes in an expansive universe of mystery, danger, and magic among the stars. Using the family d20 engine, Starfinder provides a plethora of character options in its Core Rules – options which it also continues to expand them with every supplement and adventure it publishes.

The Starfinder RPG is a tabletop roleplaying game by Paizo Publishing which presents a science fiction / fantasy universe set firmly in the sub-genre of space opera. Taking place ostensibly thousands of years after the Pathfinder RPG, players in Starfinder are adventuring heroes in an expansive universe of mystery, danger, and magic among the stars. Using the family d20 engine, Starfinder provides a plethora of character options in its Core Rules – options which it also continues to expand them with every supplement and adventure it publishes.

As a d20 product, the game is highly approachable for novice and experienced tabletop players alike. It also provides a steady escalation of complexity as groups of players proceed through a narrative campaign, allowing a copious options for customization and personalization as the characters advance. Anyone familiar with a d20 / OGL product should be able to quickly pick up the game, though it does very much favor the more action-forward, narrative-driven form of storytelling over the table-heavy, every-modifier-counts rules intensive style of some d20 games. The hardcover of the Core Rulebook can be ordered online through Amazon or through Paizo’s website, and the latter also has a PDF option at a much lower price point.

With the Core Rulebook, players and a GM can play seven new races, seven full classes, and a wide selection of the finer bits every d20 game loves. Spells, Feats, Skills, and various Class Features are on full display, along with a wide variety of monsters. Mechanics are given for loot in all its myriad forms, along with simplified rules for chase sequences and dynamic vehicular combat. All in all, Starfinder is a more than sufficient entry point for players looking to get involved in science fiction roleplaying while still incorporating enough of the more traditional RPG fantasy elements that it should still feel very familiar.

With the Core Rulebook, players and a GM can play seven new races, seven full classes, and a wide selection of the finer bits every d20 game loves. Spells, Feats, Skills, and various Class Features are on full display, along with a wide variety of monsters. Mechanics are given for loot in all its myriad forms, along with simplified rules for chase sequences and dynamic vehicular combat. All in all, Starfinder is a more than sufficient entry point for players looking to get involved in science fiction roleplaying while still incorporating enough of the more traditional RPG fantasy elements that it should still feel very familiar.

It is one area in particular, however, where the game truly sells itself as a highly vaunted science fiction RPG: Starfinder has the best rules for starships that I have seen in a tabletop game, and it is this element alone which sold me on it above all others. I had been seeking a game with robust, engaging rules for starships for years; I just never knew it.

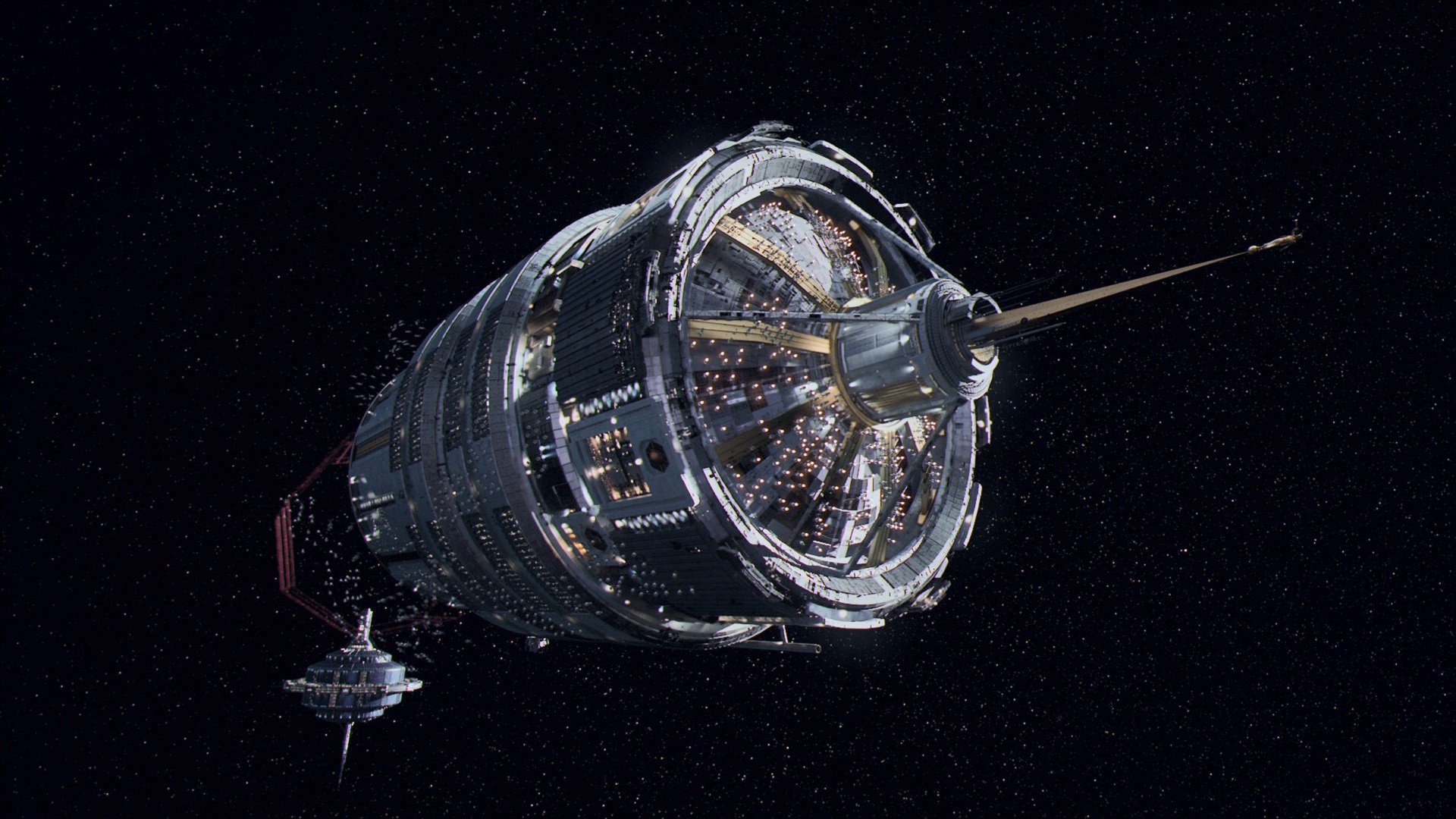

Wagon Train To The Stars

It is impossible to imagine space opera without starships. Whether it’s a master-class flagship such as the Enterprise, or a slapdash bag of bolts with a heart of gold like the Millennium Falcon, starships are iconic to space opera, regardless of their medium. Both versions of Battlestar Galactica are named for the starship they take place on, and Firefly boasts its model name as a series title, with its personal name of Serenity as its film title. The starships of Babylon 5 are unique to each of its races, and what would The Expanse be without starships like the Rocinante, the Behemoth, and the Canterbury?

In many space operas, starships serve as more than simply a means of transportation, getting the characters from point A to point B. The starship is a home that travels with you, the ultimate gateway to the stars, serving as both refuge and protector. In many space operas, the starship is very nearly a character unto itself, with many an engineer waxing poetic about how this particular ship has its own being. This can even be taken to the extreme, with a living ship like Farscape’s Moya being a character within the show itself, complete with her own wants, needs, and character growth. In order to capture this part of space opera right, an RPG needs to approach the starship like its very own character.

And that is exactly what Starfinder does.

The Gameplay

Using a system of points dependent on the overall “level” of the starship, players can customize their starship to be anything from a clunky freighter trying to get them to the next port of call, to a capital class warship, bringing devastation and / or protection across the stars. In Starfinder is assumed that a starship will be of the same level as the Player Characters, and it grows alongside them – reflecting the hours of hard work, lucky deals, and mysterious upgrades the player characters put into it.

Using a system of points dependent on the overall “level” of the starship, players can customize their starship to be anything from a clunky freighter trying to get them to the next port of call, to a capital class warship, bringing devastation and / or protection across the stars. In Starfinder is assumed that a starship will be of the same level as the Player Characters, and it grows alongside them – reflecting the hours of hard work, lucky deals, and mysterious upgrades the player characters put into it.

Players can, of course, choose to trade out their starship as they outgrow it, but the access to your “standard issue freighter” that can be a home for a crew of six is available from the very start of the game. While this could lead to an interesting Ship of Theseus question down the line in a campaign, the fact stands that the game operates under the basic and central premise that the PCs are the crew of a starship.

The equipment of the starship covers both mundane and faster-than-light travel, with accessible rules for each, along with an engaging set of rules given for the exact operations of a starship’s crew.

Player Characters can act as a starship’s engineer, for instance, interfacing with the engine to push its efficiency up just a little bit more. The pilot directs the starship’s movement, leading it through any number of intricate maneuvers to gain an edge. A starship’s Captain can pinch-hit for any of the other roles and is given special actions to motivate and direct their crew…or taunt their enemies. Characters acting as a Science Officer can operate a starship’s computer to run sensor sweeps, open communications, and provide target locks to the characters working as the starship’s gunners. And the job of that last part should be fairly obvious.

Hand in hand with these class-based systems, which allow you to customize every little bit of a starship’s design, is a hex-based space combat system. As with any combat system, Starfinder does tend to get a little clunky in this regard, and careful design and implementation should be taken to ensure that no job in the starship goes unneeded on a given round of combat – if only to keep players engaged in the fate of their characters. While this is the ideal, as with any game system, what sees actual play will always be different. Largely good, but different.

The Takeaway

While many games have given some form of rules to build, customize, and engage in combat with starships, I have not seen a game where the system is as complete and approachable as the Starfinder RPG. It is specific where it needs to be specific, expandable where it needs to be expandable, and perfectly balanced to switch between cinematic and tactical when the situation calls for it. Above all else, Starfinder gives you the room as a player to work with friends to crew a starship together, where each can add their own little pieces to it here and there, creating your own little slice of home that can journey with you into the stars and beyond.

And from all the way up here, it is one hell of a view.

David Gordon is a contributor to the site. A storyteller by trade and avowed tabletop veteran, he is always on the lookout for creative tabletop games. He can be reached on Twitter.

You can discuss this article and more on our social media!

Photo Credits: Starfinder images by Paizo Publishing; Star Wars by The Walt Disney Company; The Expanse show image by Alcon Entertainment