When Hollywood makes a movie with an expansive budget, big-named actors, and special effects that will impress the most stingy critics, they have to get the green light from some deep-pocketed studios.

Well, you are not part of one of those studios, nor are you one of those actors – yet. You took some classes at the annex though, and you’ve decided that now’s the time to make your entry into the big time.

So here you are, on the lot of Deadwood Studios. It may not have money, or fancy sets, or reliable catering. There’s a chance the camera might not be working 100% of the time, and Ray the gaffer is more than a little creepy. Still, you’re finally going to make your mark. You’ll have to start out with some bit parts, but maybe, in time, you can be the star. Besides, how tough can being a cowboy be?

The Premise

“Can we get a for replacement Town Drunk? I’m not sure I’m buying he’ knows what to do. He’s actually drunk? Well then, keep rolling!”

It’s filming time at Deadwood Studios, a less-than-stellar western movie backlot. Conveniently, players start off as less-than-stellar actors.

Players navigate around the sets, taking jobs as actors and extras in the hopes of getting a little extra cash. Players are hoping to make as much money and fame as they can for themselves by honing what little talent they possess through several days of shooting.

The Rules

Deadwood Studios is a thematic movement game, wherein players venture around to various board locations. Setup is quick and simple. The board is modular, with four sections that can be arranged in a number of ways, though the default layout is displayed in the rules. Each player receives a player marker – being a colored d6 – and places them at the Trailers. Players then set their dice to level 1, signaling their current rank. Player size alters some starting conditions, so you’ll want to consult the rule book for your party size.

The starting player is determined randomly. Turns are played out over a number of rounds, called Days. At the start of each Day, on each set location, place one Scene card face-down and between one and three Shot Markers on the appropriate spots.

At the start of a player’s turn, they may move one space and/or take on a role. The first player onto a set flips over the Scene card and reads the text (out loud preferably). They then decide whether or not to take one of the roles offered.

There are two kinds of roles available: Leads and Extras. In order to take a given role, the player’s level must meet or exceed the level of the role. Lead roles are those listed on the Scene card; Extra roles are those printed on the game board. If a player takes a role, they are locked into that space until the scene “wraps”.

If a player starts their turn on a role, they roll a die – not to be confused with the player markers. If the number rolled meets or exceeds the budget number on the top right of the Scene card, the shot is complete, and a Shot Marker can be removed from the location. Completed shots are how players get paid. Extras who complete shots receive one Fame and $1. Leads receive two Fame.

On the other hand, if the number rolled is less than the budget number, not even the pitiful directors of Deadwood Studios consider it a job satisfactorily done. An Extra still collects $1 (since they mostly just expect you to show up). However, a Lead collects nothing. To offset higher difficulty roles, players can opt to forgo rolling for their turn and instead take a Rehearsal token. Each Rehearsal token provides a +1 to any dice roll, and they are good for the duration of the scene.

Once the last Shot Marker is removed from a scene, that scene is complete. Lead actors are provided with a bonus. The player who completed the scene rolls a number of dice equal to the scene’s budget and arranges them such that the highest value is matched with the highest level role (even if that role is unoccupied), the second-highest with the second-highest role, and so on. If more than three dice are rolled, the dice wrap around and start again back at the highest level role. The total value of the dice associated with a given role awards that much money to an actor. Extras get a wrap bonus of money equal to the difficulty level of their role, but only if a scene contained a Lead actor as well. Otherwise no bonus is awarded. The scene is discarded, and those players are once again free to move around the board.

Here, Blue gets $7 for his brilliant rendition of getting hit with a table, and Green gets $2 for being on fire.

Besides the film lots is the Casting Office. It is here where players can spend either money or fame to increase their rank. Leveling up lets your actor take more lucrative roles.

Once all but one scene wraps, the Day is over. A new Day starts by moving all players to the Trailers, replacing the Shot Markers, and placing new Scene cards.

At the end of three or four Days (depending on players), players tally up their score. The player with the most points wins. Their reward is a trip off of Deadwood Studios and on to grander things. The rest should grab a script, because Jimmy Fell Down a Well IV is about to start soon.

Giving It Your All

Cheapass Games historically made a name for itself by providing a host of worthwhile low budget games. They have traditionally been light on production quality and components, opting to provide just the core of their games at modest prices. Cheapass Games would only sell the essentials of what was needed, letting (or forcing) players substitute pieces from other games to make it work. Games made by Cheapass therefore became known not for their physical detail but for the thematic elements the games possessed.

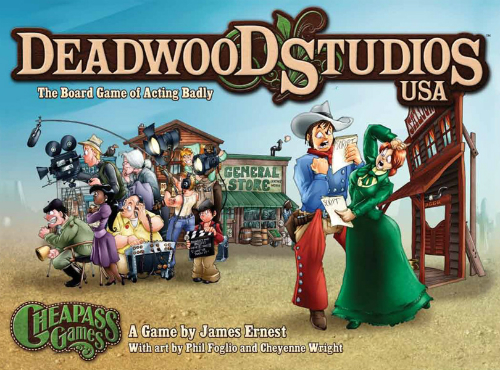

Deadwood Studios, USA, is effectively a reboot of one of these earlier games. Many rules and components have been upgraded and retooled, such as colorful (though often obscured) artwork by Phil Foglio, and while it is a marked improvement over its predecessor, the physical aspect is not what will draw people to it. This is still a “Cheapass game”: the card stock is fairly thin, the tokens are basic punchboard pieces, and the player dice markers are still, well, d6 dice. No, instead, Deadwood’s draw is in its flavor.

The scenes revealed throughout the game each have their own amusingly creative text. Deadwood not only encourages players to read the flavor material when revealing the card or attempting lines, but it is a central part of the game’s enjoyment. If you remove its western imagery and skip the more roleplay-friendly antics, Deadwood is just players making a success/fail roll.

Why is there Leprechaun in the General Store? More importantly, why is being a Startled Ox more difficult?

Beneath its light mechanics, Deadwood is basically an involved party game. The rules are very quick to grasp, it’s light enough to encourage the interaction of upwards of 6-8 players, and the focus is heavily tiled towards how player’s interact with the game. The more responsive your play group is to the game’s C-grade western ambiance, the better it will be received. Deadwood does not impose a requirement to partake in the flavor, but we recommend getting into the spirit of it for full effect. In most group settings, the payoff will be worth it. Deadwood is certainly lively enough for Socializers but also encourages the Immersionist in all of us to take up the card and try to give the best “Dangit, Jesse!” or, “You shot my guy!”, or “Ow!” that you can.

There’s A Hole In My Bucket: Take Four!

A variety of quotes in existence boil down to the simple meaning that life is a journey, not a destination. The same applies to social games like Deadwood. Most of the enjoyment stems from the experience of progressing through the game rather than trying to win (although there’s nothing wrong with trying). The principal mechanic in the game – advancing the scene through dice rolls – is a very random one and is hard to plan around. It can be offset by Rehearsal tokens, yes, but luck remains the driving force on how a player fares. In short, this is not a game for Tacticians. The most complex thing you do is gauge when best to spend resources to upgrade at the Casting Office; attempting to strive for more will only frustrate them. Likewise, Strikers too would be wise to sidestep this one since much of the outcome is beyond their control, and the only real impact one player can have on another is stealing a role.

While a Striker may usurp a role as a calculating way of blocking someone (such divas!), the Daredevil would probably do it simply because they really wanted the part of Unlucky Pete. Or Squinting Miner. Or Ape King. Or Cowbot Dan. Or A Horse…

You get the idea.

Yes, Daredevils should thoroughly enjoy the bizarre and strange western scenes that Deadwood Studios is known for. This is especially true for Daredevils with a fondness for dice and/or those who enjoy a bit of flair to their decisions. Don’t be surprised if this group abandons early any inkling of attempting to win, instead opting to get in on some of the most ridiculous westerns imaginable.

Deadwood Studios is a very surface-level game, and it’s evident early on which players are alright with this and which aren’t. Except for your resident Architects.

The main thing that will catch their attention is the variable board layout. Deadwood’s four game boards are arranged in a rectangle pattern by default, but your version of the backlot can be any arrangement you wish so long as the doors line up. You can have your studio be a single row, making it a long march to the Casting office from the Trailers, or you could literally have them adjacent to one another. There are a great number of permutations available, and this variable setup will be appealing to them.

Additionally, they may also appreciate your actor growing and advancing through “the process”. Players do advance by leveling up, and the win mechanic is based around accumulating the most money and fame. However, have to trade money or fame to get that promotion, and parting with hard-earned resources is not something that comes easy to this group. On average, Architects will be skeptical of Deadwood. Those who shade closer to ligher game styles could warm up to it, but don’t be surprised if many of them pass on future playthroughs.

The Takeaway

Deadwood Studios is not a cerebral game, nor does it pretend to be. Instead, it continues the Cheapass Games model of providing fun, light games to a wide audience. Deadwood is unimposing, engaging a fair number of players in joviality with still enough substance to feel like something of consequence is happening. It competently bridges the gap between the often highly chaotic nature of a party game and the light strategy of your average Gateway Game. The result is one that’s light on rules but very heavy on cheeky flavor. The satirical take on substandard movie lots, westerns, and acting in general is inescapable, and the degree to which you embrace that is left up to the player. Deadwood Studios, USA is a lightweight and accessible option for people seeking a good social game without going full-tilt into party game territory, and it plays about as quickly. If that sounds like something you’d be interested in, saddle on up and check Deadwood Studios out.

Deadwood Studios, USA is a product of Cheapass Games.

Cardboard Republic Snapshot Scoring (Based on scale of 5):

Artwork: 4

Rules Clarity: 4.5

Replay Value: 4

Physical Quality: 3

Overall Score: 3.5

Photo Credits: Office Space by 20th Century Fox.