“You got a job, we can do it; don’t much care what it is.”

– Captain Malcolm Reynolds

The Premise

Life outside the central core planets isn’t easy, but it’s a life where folks can make their own choices – for better or worse. Taking place within the Firefly universe, players each find themselves in command of a Firefly-class transport vessel. Traveling to different locations, players pick up work, upgrade their equipment, hire crew, and see about earning a tidy profit, all without running afoul of the authoritative Alliance or the deadly Reavers. It’s simple really: do the job. Get paid. Keep flying.

The Rules

Firefly is a pick up and deliver game on a massive scale, and the game’s contents reflect that. As a result, Firefly requires a significant amount of room for the main board, player boards, card decks, money, and numerous other resource stacks.

To begin, each player receives a ship board, fuel, and some starting money. Players also receive one Contact card from each of the five Contact decks, keeping three of them. The starting player is chosen randomly. Then, each player selects a captain card and places their ship at a location of their choice.

Lastly, players select the game’s Story card. The Story card explains the game’s scenario and specifies the goals players must accomplish to win the game.

Firefly plays out over a series of turns. Each player’s turn consists of taking two of four available actions: Fly, Buy, Deal, or Work.

An Alliance territory event card.

Flying moves the player’s ship. Players can either move to an adjacent sector at no cost or spend fuel and move up to their ship’s movement speed. When expending fuel, the player draws and resolves an event card from either the Alliance or Border Space decks upon entering each sector, respectively.

Buying allows players to purchase equipment and ship upgrades, stock up on fuel and parts, and hire new crew. If a player is at one of the five Supply Planet locations, they may select up to three cards from its deck and / or discard pile and purchase up to two of them. These items and crew provide a variety of abilities that are useful for resolving events and performing jobs.

Dealing lets players attain new jobs to do. If a player is on one of the five Contact locations, they may select up to three cards from the deck and / or discard pile and may keep up to two of them. A player can’t have more than three active jobs and three inactive jobs. If a player has completed a previous job for the Contact, they are considered “solid” with them, awarding a special ability and allowing them to sell excess cargo.

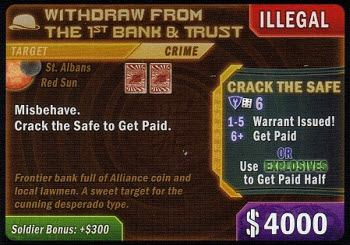

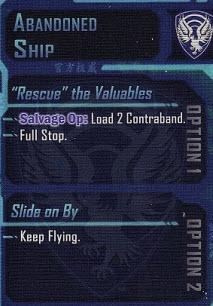

Working is the act of starting or completing a job card or Story goal. A player Works the job by being at the stated location. Most basic jobs and events require passing certain skill checks (Fight, Tech, or Negotiate) in a simple Success / Fail manner. The player rolls a d6, adding any bonuses from items and crew, and checks against the challenge outcome. Any time a six is rolled, they get an additional roll.

Many jobs and Story goals also require players to get their hands dirty. This involves drawing event cards from the Misbehave deck and resolving tougher skill checks, some of which require specific items. If a job is successful, the player gets paid.

Players continue taking turns until one person completes the final Story goal. That player’s crew are henceforth known as the Big Damn Heroes.

Everyone else should just keep on flying and consider themselves lucky they aren’t Reaver bait.

It Sure Looks Shiny!

Part of the appeal behind Licensed Games is that people familiar with the source material can interact with and appreciate an idea they already enjoy in a new way. You don’t have to learn the intricacies of a whole new fantasy realm if you’re in one you’re already familiar with. Yet the reverse of this also holds true. That is, licensed games can become so insular in trying to be faithful to the material that they lose appeal to the wider gaming community.

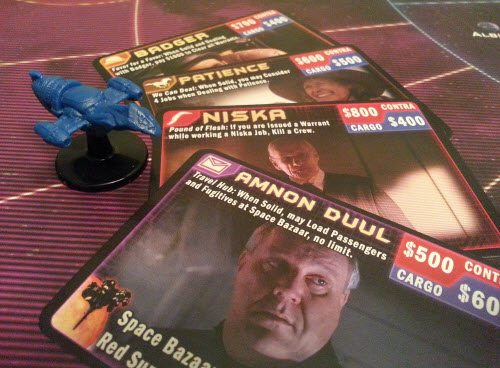

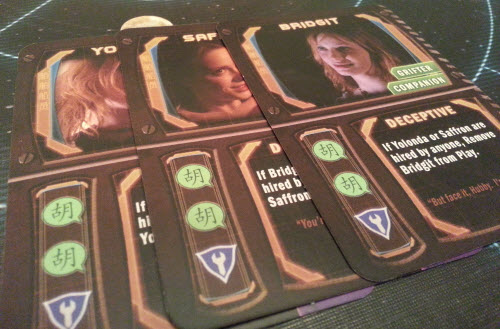

Firefly does not fall into that trap. In fact, it seems to be of a split mind as to how much of the show it wants to inject. For instance, many of the items and all of the named characters in the game are depicted via screen captures from the show. So only those familiar with Monty, Nandi, or Jubal Early will gain that added appreciation of seeing them in the game.

However, they also functionally work regardless of who they may be. There is zero in-game advantage of knowing who Badger is when deciding to take one of his jobs.

But Firefly splits its artwork evenly between unique graphic design and photos from the show. All of the poster-style depictions on the back of the Supply decks is particularly impressive, as is the money, and the design work from the event and job cards to the ship placards is clean and flavorful.

This juxtaposition of style can cause a bit of a disconnect at first, especially if you’re averse to seeing screenshots in games to begin with, but for many this dissipates after several playthroughs. It also unintentionally proves that Firefly is substantive enough that it doesn’t have to rest on the laurels of its source material to be a rewarding game.

This juxtaposition of style can cause a bit of a disconnect at first, especially if you’re averse to seeing screenshots in games to begin with, but for many this dissipates after several playthroughs. It also unintentionally proves that Firefly is substantive enough that it doesn’t have to rest on the laurels of its source material to be a rewarding game.

By combining its visual elements with concise mechanics and variety of Storyline elements, Firefly yields a wholly formed game experience that pays homage to the franchise while firmly standing on its own merits. Indeed, Firefly would still be a worthwhile game even if it was a wholly unique setting. Immersionists will appreciate this cohesion, Firefly fan or not.

Alone in the ‘Verse

Space is big. Huge. Mind-bogglingly gigantic. As a percentage of the Milky Way galaxy, our solar system is effectively 0%. If each star in the known universe were a grain of sand, to count them all would require more than all of the sand on all of the beaches on Earth.

It’s really, really big.

If you see this ship, run.

Even in the Firefly system, with dozens of planets and a concentrated pockets of civilized space flight, it’s not only possible to journey along without running to other ships, but it’s pretty likely.

This is reflected in the game too, as players will spend most of their time moving around the board without running other players. Firefly is predominately a Tableau game, where everyone is effectively commanding their own crew, having their own encounters, and progressing through the Story individually. This solitaire-like play style highlights both the game’s best attribute and most notable area of criticism.

On the one hand, Firefly wonderfully plays out each player’s tales of thrilling heroics, where you and your band of misfits move about largely unencumbered. It’s not that you can’t interact at all with other players (or Alliance and Reaver ships for that matter), but it plays a minor role in the game. Instead, your focus is on answering questions like: do you take on riskier jobs for a better payout, or settle for simple deliveries? Do you spend what money you have on upgrades, new crew, or a fancy hat? Is working with Niska worth the potential ramifications?

Firefly seamlessly blends this narrative-driven experience and its mechanics together. When your ship breaks down, it’s up to your technology to fix it, and when things go wrong planetside, a quick draw or a quicker tongue can help you pull through. Firefly wants you to feel like you’re part of the existing landscape, and it does so handily. This is an ideal game for Architects, where they are free to build up assets, explore the ‘verse, and make a run at the finish line without the entanglements of other players.

Daredevils should also enjoy this ride through the Black. There goal of each game is the same – finish the Story – but how you get there is part of the fun. You can’t win the game without at least a little gambling, so count them in.

On the other hand, Firefly’s conflict-averse style creates measurable downtime between turns. While one person is off having their adventures, everyone else must wait. So…consider yourself on a commercial break. With only two actions, turns can go by very quickly, but they can also drag on if a player is rummaging through a Supply pile or reading their various job offers. That said, unless it affects the next player, it doesn’t hurt to let play continue whilst you decide. The rulebook even suggests scouting out cards ahead of time, though this tacitly acknowledges that downtime can be an issue.

Even if players are brisk with their actions, though, Firefly will take a while, and it’s not uncommon for the game go beyond its advertised two hour timetable. Thus, even while it’s not a complex or combative game, Socializers should pass on it unless they are diehard Browncoats.

Escape Velocity

While the tableau style offers a rewarding experience on an individual level, the lack of player interaction can also foster runaway leader issues. If you can far enough ahead of other players in terms of upgrades and Story progression, you can reach a point where, barring a long sequence of event failures, your victory is all but assured. Watching another player fail to Misbehave multiple times is the best recourse you have to catch up if someone is far ahead. With one exception, you can’t affect a player’s chances or take anything from them – sky or otherwise.

While the tableau style offers a rewarding experience on an individual level, the lack of player interaction can also foster runaway leader issues. If you can far enough ahead of other players in terms of upgrades and Story progression, you can reach a point where, barring a long sequence of event failures, your victory is all but assured. Watching another player fail to Misbehave multiple times is the best recourse you have to catch up if someone is far ahead. With one exception, you can’t affect a player’s chances or take anything from them – sky or otherwise.

In Firefly, the ‘verse can be a place of ill timing and misfortune. The randomness of the game’s events can often be mitigated with the right cards or die results. Even still, there will also be occasions where, regardless of the amount of planning, you will lose. You simply can’t be fully prepared for every event that you come across. Sometimes luck will just not be on your side, and it’ll trump your gun-toting wisecracking crew.

For these two facts alone Strikers should seek passage elsewhere, as Firefly is exact opposite of everything they look for in a game. Some Tacticians may do the same. While the game offers up strategic choices over which jobs to take and which stops to make, there isn’t a lot of long term planning beyond working towards the victory condition. Firefly captains instead hop from one job to the next in a zigzag to the finish line. Still, even if you can’t be positive where you’ll be bound for after the next job, there are plenty of important logistic decisions to make.

Nonetheless, while you can offset the influence of the die results by acquiring new crew and items, luck is as inescapable in Firefly as the Alliance eventually meddling in your affairs. Ironically, which assets you can get to help in this regard is largely luck of the draw. Being able to pull cards from the discard piles instead helps, but there’s no guarantees you’ll find exactly what you want. In many cases, though, you may find exactly what you need.

The Takeaway

From takeoff to touchdown Firefly is an adventurous pick up and deliver game fraught with the perils and excitement of life on the outskirts. One moment a player may be cruising along, and another they’re on the run from the gorram law. Regardless of your attachment to the source material, Firefly is sound enough that the show’s impact on its overall worth ranges from negligible to an added bonus. Firefly: the Game could even function perfectly well without the Firefly theme.

The game is straightforward, turns are simple, and although much within the game is determined by a die roll, one never feels completely at the mercy of luck as careful planning and the right crew can help you through almost any situation. That said, because of its combination of length and an almost completely non-interactive nature, this is not a game for conflict-driven players or anyone looking for fast-paced action. However, for those seeking a game where the emphasis is instead on manning a ship and controlling their own destiny, Firefly is one that they will be very solid with.

Firefly: The Game is a product of Gale Force Nine.

Cardboard Republic Snapshot Scoring (Based on scale of 5):

Artwork: 3.5

Rules Clarity: 4.5

Replay Value: 4

Physical Quality: 4

Overall Score: 4