There’s no time for introductions, lad. Welcome to the Royal Detective Bureau here at Scotland Yard. We’re on the heels of Mr. X…there he goes! After him!

The Premise

Mr X, the notorious criminal, is on the run in London. One player fills the role of Mr. X, trying to escape capture by Scotland Yard. The other players are detectives, working collectively to catch Mr. X before time runs out.

The Rules:

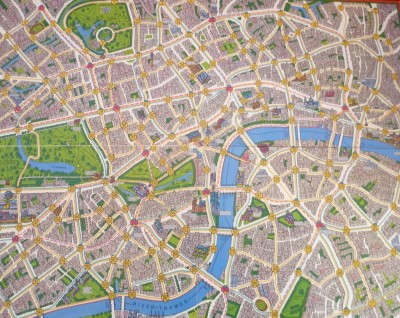

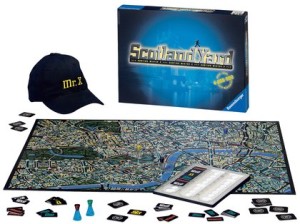

Scotland Yard takes about the setup that you expect for any classic board game. That is, there’s very little time involved. The board itself is a layout of central London, complete with 200 different points. The game can take up to six players. One player volunteers / is designated to be the dastardly villain Mr. X, and the remaining five detective roles are doled out depending on the number of players. (All five detectives will always be used.) Detectives each randomly receive one of eighteen cards that tells them their starting location. Mr. X also receives one, but their starting location is kept secret. Additionally, each detective receives a finite number of 22 fare tokens: 10 Yellow Taxis, 8 Green Buses, and 4 Red Underground. Mr. X, on the other hand, has an unlimited pool of those fares. Additionally, the Mr. X player also receives the special Black Tickets and 2X tokens. More importantly, they also receive a ledger that they will use to track their movements throughout the game.

Turns always start with Mr. X and proceed clockwise around the table. The Mr. X player will take a fare token from the pool tokens and secretly write down on the ledger the spot they are moving to. Then they place the type of fare they used to move on top of it. Each of the 200 spaces on the board can be accessed by one or more types, depending on the color(s) shown for that space. There are also color-coded lines between locations to let you know if travel is available between two points. Detectives then use their fare tokens to move their pieces about the city.

Mr. X has two bonus tokens available for use that the detectives don’t. The Black Tickets allow Mr. X to either disguise which mode of transit they took for the round, or they can be used for traveling by water on a few select spaces. The two 2X tokens are used to allow Mr. X to take back-to-back movements. Unlike the normal fares for Mr. X though, these special types are limited. Use them wisely.

At five points in the game, Mr. X reveals themselves for one round, cluing the detectives in on his whereabouts. Players must coordinate their efforts when this happens; if Mr. X is not caught after the fifth time, he escapes and that player wins. If at any point in the game a detective lands on the spot where Mr. X is hiding (or if Mr. X accidentally moves on to their space), instead he is caught and the detectives win.

The Early Years

If you walk into your local game store, you may see Scotland Yard on the shelf under the Ravensburger label and unsuspectingly think it’s a new game. It isn’t*. In fact, Scotland Yard turns 30 this year, making it one of the oldest widely successful board games not to come out of America. Our review here pertains to the Milton Bradley version released in the US in 1985, and while the newer edition from 2004 modernizes some of the board and pieces (somewhat), there isn’t any other changes. The reason the game is still being sold really comes down to three factors:

1. It fits the criteria for a family board game. Scotland Yard is quick to set up, quick to explain, and can involve a decent amount of people. Plus, it’s relatively short, which is always key when doing family games. Mr. X is undoubtedly the trickier role to play, but even then it can be worked out. The detectives need to work together to stop Mr. X, and what’s better than having the kids team up on one of their parents?

2. It was one of the first to experiment with the idea of co-ops. It’s hard to think of it now in the Age of Co-Op Games, but if you think back to the classic games you had as a kid (Risk, Monopoly, Clue, Life, etc.), they all follow the same RAM pattern: Roll And Move. Roll a die/pop a bubble/spin a spinner, then go that many spaces, then do something. Scotland Yard helped to expand on the idea that there was more to board games than that. Notice, for example, that there are no dice with it.

That alone made it different, and it should be no surprise it was one of the early Spiel des Jahres winners. Sure, other games would go on to refine the idea of a purely “Players vs The Board” genre. Yet games like Scotland Yard, Fury of Dracula or Heist (er, I mean Clue: The Great Museum Caper) became a type on to themselves. They are asynchronous games revolving around one player being the antagonist, and clearly there’s still a market for players opting to be the Big Bad Guy. Otherwise companies wouldn’t keep making them.

3. The nostalgia factor. Most of us start playing board games as a kid, because, hey, these are fun! Games embody a form of entertainment that is social, economical, and it taps into our instinctual desire to explore new places. Those things don’t just disappear as we get older. Rather, the reason so many people drifted from gaming back then was that for years there was a heavy stigma in society that if you’re spending your Friday night playing board games, you must be boring, antisocial dorks – even if most gamers know that the community is quite the opposite.

That stigma has waned some in the last decade or so, but it was still prevalent in the 80’s and much of the 90’s. Those same people who remember the excitement of uncommon games from their past like Scotland Yard or Survive! often have a strong sentimental reaction when they see them back on store shelves. And with good reason: publishers don’t reprint games unconditionally, and they certainly won’t reprint bad ones. If they’ve decided it’s worth bringing back, you’ll get a sense of nostalgic vindication that, even decades later, your choices in games had merit. Scotland Yard is one such game.

Because I Said So

You’ve probably encountered this kind of child before, the one that will pepper you with the same singular question over and over again: “Why?” Some do it because they’re actually inquisitive. Others do it because they find it funny to exacerbate people. Well, until the run into the brick wall of an answer: “Because I said so”. It doesn’t make a lot of sense at times, but it works.

Of course, that tactic is great for an incessant eight-year-old. It does not, however, work as well on older folks.

Nor does it bode well to be continually asking that when playing a game.

And it’s even worse when it pertains to the central theme of your game.

Having someone question why a certain game mechanic works that way or why a designer uses one style of resource management over another is a healthy debate. Having someone question a core concept of your game is a red flag. What’s more, if an Immersionist is doing that, you’ve probably lost them all together. Such is the case with Scotland Yard.

Now, Scotland Yard has a lot of things in its favor. It’s engaging with other players and contains a simple ruleset that will make Socializers happy. The objectives are evident, and you don’t get a lot of player interference or random curveballs thrown at you. Thus, you are pitting your deductive reasoning, skill, and luck against the other player(s). Strikers will be happy in either role. Additionally, while you may not be building complex machines or creating clever combo moves, you often you have to think ahead and continually reassess your movement choices – especially as Mr. X. In addition to replay value, this strategic planning will keep Tacticians engaged – though they will likely much prefer to be the villain.

For all that though, there are a couple of glaring thematic holes that can spill over into gameplay.

- Why do the police have to take public transportation everywhere? Do they not have their own cars?

It’s sort of the big mechanic to the game: you only have 22 fare tickets. If you misappropriate them, you will find yourself stranded late in the action. So why are the police handicapping themselves here?

- Why can’t the police walk on foot?

So you’re on a space, and you’re pretty confidant that Mr. X is the next block over, why should it matter whether or not you still have Taxi / Bus tickets left? Couldn’t they, you know, run? If Mr. X is such a high profile target (so much so that he doesn’t actually have a name beyond “X”), is being out of cab money going to stop true detectives?

To most other archetypes, these are minor facts that won’t detract from the larger picture. And it’s true, if an Immersionist can overlook these facts, it’s engaging enough conceptually for them to enjoy either being the master criminal or a team of police, albeit on a surface level. In general though, most can’t. They will be dogged by those design holes, and it’ll be hard to keep them engaged. They may be power through the first time, but replay value for them will be very low. Architects are also likely to take a pass on this game as well since the things they tend to enjoy (character building, item gathering, territory expansion, etc.) are just not present.

The Takeaway

Scotland Yard won the Spiel in 1983 for good reason. That said, that was 1983. It’s a bittersweet fact. On the one hand, the explosion of gaming as a hobby, and the continued gaming evolution is a direct result of early successes like this. On the other, the gaming world has become much more refined, and trying to compare this game to those of today isn’t quite fair. It won’t be able to stack up to the nuanced gameplay, production quality, and intricacy of so many games of recent years.

The simple response to that is: don’t. Don’t approach Scotland Yard as a modern game with problems. Approach it as a classic game that offers so many of the things that got your younger self interested in games in the first place. Yes, it has a couple issues, and like most games pre-Settlers of Catan, it has a pretty basic pretext. For most though, there’s still plenty to enjoy in this style of hybrid co-op gaming – an 80’s game that avoided the Monopoly/Risk mold doesn’t sell 4 million copies because it’s bad.

So pick up the challenge and see if you have what it takes to be Mr. X (or capture him). Whether a relatively quick game with friends, or for a family game night, Scotland Yard has become a symbol of where gaming as a hobby came from and where we’ve gone since. It also happens to be a decent mad dash around London, even if you’re not dashing about on foot.

* In truth, Ravensburger has actually handled distribution of the game in Canada and Europe since it originally came out.

![]()

Cardboard Republic Snapshot Scoring (Based on scale of 5) and based off the pre-2004 versions:

Artwork: 2.5

Rules Clarity: 5

Replay Value: 3.5

Physical Quality 3

Overall Score: 3