Nowadays, the vast majority of the items we see around us are mass produced: they are machined, processed, packaged, and shipped with such uniformity and precision that you’d never be able to tell one designer from another. Prior to the Industrial Revolution though, the world was a very different place. Craftsman were in charge of their domain, both as shrewd business owners of their trades and as keepers of the knowledge to their skills. To most of them, their trade was equal parts job, hobby, and work of art. Their work was a source of money and of honor.

Today, many things are different. As consumers we think of craftsmanship as customized or personalized projects that can’t be done on a large scale. What hasn’t changed, however, is that sense of exalted pride those artisans feel when they complete that worthwhile task…

The Premise

In an old Chinese town, several master craftsman are vying for the prestigious title of Zong Shi – The Grandmaster craftsman. Achieving this title will not be easy, as players are competing with one another for the honor and status that this title bestows. Players must choose how they will go about demonstrating their superior skills, as they look to prove that they are indeed the most deserving.

The Rules

In Zong Shi, players act as both the master and the apprentice of their craft. To that end, each player receives a Master token, an Apprentice token, visit markers, and a placard representing the player’s workshop. The board represents the town in which players live and practice their craft, and setup for it is very quick. The first player is determined randomly. Then, after placing the respective cards, tokens, and boxes of materials in the locations stated in the rules, a random assortment of material boxes and Scrolls of Fortune are distributed out one at a time until are are taken; these become each player’s starting resources.

Each round consists of players placing their Master and Apprentice at one of the four locations on the board. Each space behaves differently depending on whether the Master or Apprentice is used:

- The Temple: This allows the player to draw a Scroll of Fortune card for free. Fortune cards afford one-time bonuses or allows players to use resources in unconventional ways when used. If a Master visits this spot, the player may purchase additional Scrolls at a cost of one box of materials per card.

- The Pawn Shop: Here players can purchase of Exchange Tiles. Each Exchange Tile has two different materials depicted on it, and each tile allows the player to use materials of one type as the other when satisfying the requirements for projects. Exchange Tiles costs one box of either of the materials of the tile. The Apprentice can purchase one such tile per visit; the Master can purchase as many the player likes.

- Respectful Visits: Visiting the village dignitaries awards victory points at the end of the game. To pay a visit, a player offers between one and three boxes of the materials as a gift. Players need only visit each townsperson once per game. The first Master to visit each townsperson during the game is given a random one-time bonus. An Apprentice may only visit one dignitary at a time. The Master is permitted to visit more than one, but the player must have the materials for each person plus additional boxes as a penalty.

- The Marketplace: This is where players receive new materials. There are two bins a player may choose from, though unlike the other locations, resources are not awarded immediately. An Apprentice will able to select one box of materials from the bin they are in, but they must wait until all Masters in that bin have already made their selections. A Master will be able to select between one and all of the materials available, depending on which other player tokens are present.

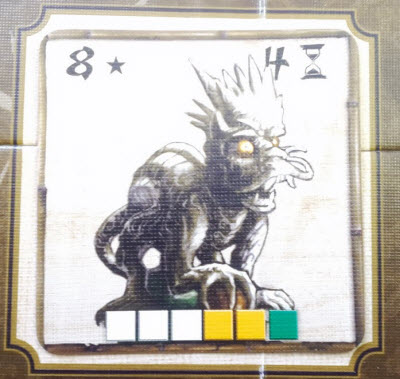

Alternatively, a Master may begin work on a project. Each project specifies its time requirement, the materials needed to begin it, and the VP awarded at the end of the game when completed. Eight of the starting projects also come with additional effects, such as the Larger Workshop, allowing for additional material storage, or Gold Mastery, which reduces the cost of projects requiring gold by one. The two Masterwork projects are longer, more costly, and provide no abilities, but they award substantially more VP at the end of the game than normal projects. Once started, the Master is unavailable for use for the duration of the project.

Once all players have placed their Master and/or Apprentice tokens, materials are distributed in the marketplace. Then, projects being worked on tick down one day towards completion. Finally, the round ends. Players retrieve their tokens from the village (those not working on projects), the marketplace is cleared and restocked, the first player marker is passed, and a new round begins. This continues until one player completes six projects. At that point, players go through one final round before scoring.

At the end of the game, Players are awarded points for just about everything. They receive VP for completed and in-progress projects, dignitary visits, exchange tiles, and potentially, unused materials or scrolls. The player with the most points wins the title of Zong Shi. All other players are forced to admit that they are inferior crafters, and that they are now full of shame.

Material Strength

At first glance, Zong Shi appears merely as another well-manicured worker placement game. It is not. Or, at least, it isn’t a worker placement in the traditional sense. Most Worker Placement games have various actions than be taken by your worker pawns, and when taken, barring occasional communal actions, it prevents other players from being able to do the same. This normal model causes players to compete for a finite number of available options.

Zong Shi is more of a Resource Management game that uses worker placement effects, rather than the other way around. The scramble is for a finite number of resources, be it projects or exchange tiles, and there are also only so many available material boxes each round. Although it has “workers”, you get two at most. (If your Master is on a project, you’ll only have your poor hapless Apprentice to direct.) What’s more, unlike most normal worker placement games, anyone can visit any of the four locations. You cannot lock out or steal a space someone else wanted to use.

In fact, as Architects will appreciate, there is little you can do to interfere with one another’s plans at all – the most you can do is muck around with who gets what in the marketplace and maybe start a project before someone else. The game tension is you trying to accomplish your objectives before other players get to accomplish theirs, lending to a civ-building-friendly setting.

Unfortunately, this means that Socializers and Daredevils will probably not find the game terribly engaging. Socializers tends to avoid worker placement games to begin with, but in tableau-style games like Zong Shi, where there is little in-game interaction between players, trying to make a foo dog statue probably won’t cut it. Moreover, Daredevils will not find the randomness and unexpected tactics that they thrive on.

Similarly, Strikers may approach the game cautiously. They like to be able to stymie opponents if it’s necessary to secure a win, and they don’t have that tool here. Of course, that cuts both ways. Even with the randomness of the Fortune cards, this is largely a game about pitting your path to victory against others, and so they’ll likely enjoy proving they are the best artisan on their terms.

Glory to the Foo Dogs

Regarding its theme, Zong Shi not only embraces it, but it deftly weaves it into both the mechanics and the flavor. The components of the game really evoke the idea of you being a master craftsman in some old Chinese village. The Masterwork projects (and the board itself) all depict Eastern art, the container for the boxes of materials is a Chinese silk bag, the first player token is a Buddah statue, and the material tokens are made of the same hard plastic material as some Mahjong tiles. But beyond that is the game’s entire premise: Masters seeking a higher status as Grandmaster for status and honor. The non-confrontational aspect mentioned earlier makes sense thematically: the players are essentially participating in a gentleman’s bet. Zong Shi does a fantastic job on this part, and Immersionists should enjoy themselves as a result.

Not that kind of apprentice.

This is backed up mechanically too. It makes sense that there is only a Master and an Apprentice, that the Masters have more pull in town, and that the Apprentices defer to the Masters in the marketplace. What’s more, while some may find the Respectful Visits a bit strange to invest time and resources into fulfilling, it’s essentially just trying to curry favor.

Fishing in the Wishing Well

As strong as the central aspects of Zong Shi are, however, there’s a couple elements that are less than stellar. The first is the Fortune cards. Part of what keeps the game balanced is that the game has a set series of actions each round. The Fortune cards allow a player to circumvent that. While you can only have four cards in hand, there is no limit to how many cards can be played in a single turn. Fortune cards grant resources, reduce construction time, allow for greater benefits from locations, and more.

The catch, of course, is that these effects are random and you have little control over which ones you draw. This would normally be enough as Fortune cards on the whole are a fair mechanic (and even a viable strategy). Yet there is a small handful that are certainly a tier above the rest and are far more powerful than others, even taking their situational use into account. The right Fortune cards can, well, change your fortune quickly.

Similarly, the Blacksmith’s Tools are far and away the best early-game project a player can get. A player’s Master is incredibly valuable, both because it’s one half of your actions for the round, but also because of the location advantages it provides.

As such, anything that reduces the time he’ll be slaving away in your Workshop is essential as it gives actions back to the player. Missing out on five or so Master turns over the course of the entire game may not sound like much, but Zong Shi is often a photo finish win. Sure, this can be offset by pushing other strategies instead, but when everyone is coveting the same project, you either have to be one of those people or quickly pivot to a strategy that can keep up without it.

Combined, these factors may give the normally worker placement-friendly Tacticians pause, at least in the long run. Zong Shi has everything this group appreciates in a solidly strategic game, but if they feel that there are only so many paths to victory, or that the Fortune cards alter the outcome of too many of the games, they may opt for a different setting after awhile.

That said, while these two areas are its loudest criticisms, neither are so detrimental as to sour the overall game’s worth.

The Takeaway

When browsing for new games, Zong Shi may not outwardly capture your immediate attention. Like many good books, however, the contents are far more interesting. From the great quality to intuitive gameplay, Zong Shi is a solid game in more ways than one. It pairs a fairly simple theme with conflict-free mechanics that offer players a variety of paths to claim the Grandmaster title. The result is a game that is incredibly flavorful but also incredibly cohesive to play. The game can be swingy at times with some of the Fortune cards, but more often than not, players edge out wins only a couple points higher than their competition, making it a race to the very end. For those who enjoy games of resource management and light worker placement, consider giving this a look. Contrary to how it may appear on the outside, Zong Shi makes for a well-crafted contest.

Cardboard Republic Snapshot Scoring (Based on scale of 5):

Artwork: 4

Rules Clarity: 4.5

Replay Value: 3.5

Physical Quality: 4.5

Overall Score: 4

Photo Credits: Darth Apprentice Worker by Wikipedia.