Things are not looking good in the land of Axia. This once proud country is in the midst of a crippling and systemic economic depression, and you’re about to be dropped smack in the middle of it. Axia’s industry is crumbling, the trade deficit is ballooning out of control, leaders are either incompetent or corrupt, investors are scared, and the government’s only recourse to keep the entire system from crashing down is to implement harsh and painfully deep budget cuts that have just as much of a chance at fixing the problem as it does making it even worse.

Luckily this is all a work of fiction and doesn’t apply to any real-world countries from which we could draw stark parallels to, right? Right.

At any rate, this is the somber setting players find themselves in with Crisis, the ambitious new Worker Placement game by LudiCreations. In this thinly-veiled allegory for the dangers of economic overreach and punishing austerity, up to five players act as entrepreneurial business folk who are practically being begged to help right Axian ship and return the country if not to prosperity (which is probably asking too much), then at least some semblance of positive momentum. You have at most seven rounds to acquire resources, start companies, hire workers, and try to raise enough financial capital to stem the tide of the country’s shaky financial instability.

At any rate, this is the somber setting players find themselves in with Crisis, the ambitious new Worker Placement game by LudiCreations. In this thinly-veiled allegory for the dangers of economic overreach and punishing austerity, up to five players act as entrepreneurial business folk who are practically being begged to help right Axian ship and return the country if not to prosperity (which is probably asking too much), then at least some semblance of positive momentum. You have at most seven rounds to acquire resources, start companies, hire workers, and try to raise enough financial capital to stem the tide of the country’s shaky financial instability.

Well, that, or try to raise your economic profile as you much can and then skip town before the whole thing collapses anyway.

Crisis starts off earnestly enough by providing many of the same fixtures you’d expect from a worker placement game, with each player receiving four Manager meeples that you’ll use during each round to acquire materials, manage resources, and if all goes well, make a tidy profit. And manage you shall; Crisis comes with copious types of raw resources, workers, companies, and other assets that you have to decide where to invest your time and effort into. Thus, much of what you do throughout the game – as well as part of its inherent appeal – is finding the best way to build a functioning economy for yourself. Buying and importing goods are possible, but they’re nowhere near as lucrative as producing goods on your own. In Axia, if you want fame, all you have to do is be self-sustainable.

To help the game establish itself as distinct within the genre – aside from its uniquely distressed setting – Crises offers a four point plan of notable aspects. The first has to do with the game’s difficulty. Although Crisis has a moderate learning curve to it, the game’s inherent complexity doesn’t lie with the rules or flow of the game. Rather, it’s due to having multiple strategic avenues to gain VP beyond focusing on Resource Y instead of Resource X. In this game, for example, you can make excessive amounts of money, or generate lots of one resource to unload onto the market, or buy numerous companies to diversify your options. Any and all of these are viable paths to victory without, which is surprising given how many moving pieces Crisis has. Crisis offers up plenty of variation and depth without being overly burdensome to players thanks to it being sparse on unnecessary rules baggage having a very systematic process, with each round broken down into five steps. It’s almost, well, businesslike. That said, it does take about halfway through your first playthrough to fully understand the nuance of what you’re doing, but from that point on the game pilots itself quite handily.

The second highlight to Crisis is the remarkable balance it has. The game uses no player scaling and has next to no variable setup. Similar to games like Le Havre, every action space, every Company, and every greasy-palmed Influence card is the same, regardless of whether you’re playing with one player or five.

The sole variable condition rests with the game’s Austerity plans, which denotes the players’ VP goals for each round, which depends solely on the number of players and the difficulty level you wish to play on. Each permutation comes with its own experience. For instance, games of Crisis in Easy mode or with fewer players behave more as an exercise in who can create the most efficient resource engine, whereas Hard mode comes off as one part mad scramble for points to keep bankruptcy at bay and one part scheming to ensure that if things do go all Enron you’ll be the one to make it out unscathed.

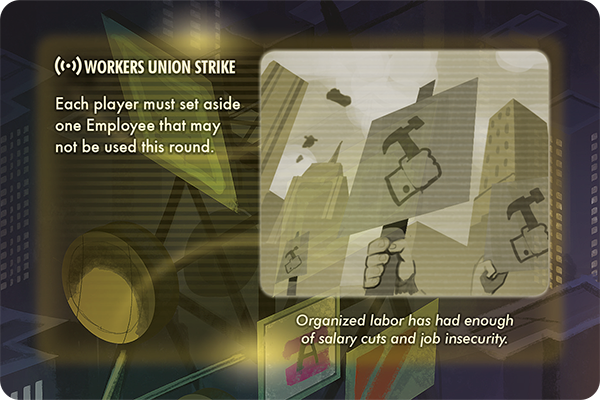

Before your Managers can start shifting paradigms and assessing the best way to allocate asset distribution though, each round begins with an Event card that provides conditions for the round, which are broken down by severity. No Event is positive (this is a crisis after all), but the more stable the country is, the less dire they are. Events add a nice bit of added flavor to the game while reinforcing the theme that the entire country could quickly spiral if things get out of hand.

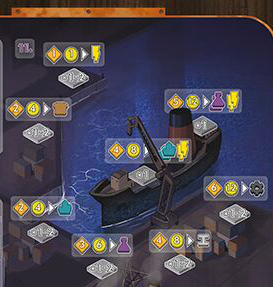

Then, players take turns placing their Managers on the plethora of possible worker spaces on the board. This board in fact:

As with many heftier worker placement games, Crisis’s board can seem intimidating at first glance due to the sheer number of potential spaces to choose from and the level of iconography depicted. With Crisis this is somewhat misleading. For a medium-weight worker placement game, Crisis undeniably has a healthy amount of substance, but it’s far less cumbersome than a snap inspection may imply as the vast majority of the symbols refer to either money, VP, or a specific resource.

To maximize planning efforts and streamline the flow of the game, everyone in Crisis takes turns placing their Managers before actions get resolved. Only once everyone has placed all of their meeples does the round move onto activating the 14 different locations on the board, which is done in numerical order. This too sounds more intimidating than it is since all but the final two locations are resolved with minimal effort.

The first four locations in Crisis either set the turn order, provide a small amount of money, and/or let you draw Influence cards. These are special one-time cards that grant you a special effect when used to hopefully undermine your competition and help you become the corporate mogul you were born to be. The next two locations, as well as two locations found later in the order focus on attaining or converting resources, such as buying food or securing a financial loan.

The most interesting part with two of these locations is that to make immediate cash or resource purchases, it requires more than just cash on hand – it also costs you valuable VP. Not only does this make sense thematically since taking out risky loans or driving up the deficit by importing goods is you working against the stability of the country, but it also highlights the third novel part about Crisis’s net worth. In this game, both money and VP are a commodity you will gain and spend. Unlike games where VP is for end scoring or always moves along a linear path, not only are your victory points continuously in flux in Crisis, but it’s practically a guarantee you’ll have to spend VP to advance your agenda. Such is the price of ambition.

The middle locations on the board are all about procuring Companies and the laborers to operate them. Companies are expensive to buy and time-consuming to gather the necessary staff and resources to power them, but doing so allows you to generate the necessary raw materials, money, and VP to forge a path ahead. These assets are the engine-building part of Crisis, and the various combinations of buildings can create some very powerful resource synergy. This all happens during Production, the second to last location and the only one to not happen on the board.

Developing and improving your Companies is one of the most rewarding parts of the game, partially because Companies and workers are permanently part of your tableau once attained. The entire process is both intuitive and fun. Every Company requires raw materials (usually) and 1-2 laborers among the game’s four different worker types. In exchange for this investment, you get the Company’s depicted output amount. However, each Company has room for bonus workers that can be assigned, which can turn your basic farm into an agribusiness with much higher yields if you land the right people to staff it. In turn, these excess resources can be unloaded at the final location on the board – the export market. There, players can sell off materials for money and VP. When leveraged correctly, a couple well-organized Companies can be incredibly profitable over the course of the game.

This Company requires 1 Worker, 1 Energy, and 1 Food during Production. Thanks to the bonus workers, it will generate 5 VP and 8 Money.

Prototype Shown

The game’s last and arguably most unique feature rests with the Financial Stability track, which is addressed at the end of each round. After everyone has resolved all of their actions, each player then compares their current VP total against the VP goal for that round, according to the Austerity card. For each victory point a player has above this goal, the track ticks upwards, showing the positive impact you’re having on the economy. For each point a player has below this point, on the other hand, the track ticks downward, as your (in)actions are burdening Axia more than helping it. If the net result of these tabulations causes the Financial Stability track to reach zero, the game ends immediately with the country going bankrupt rather than playing out all seven rounds.

Hey, no one said capitalism was friendly. That’s sort of how Axia got in this position in the first place.

Red exceeded the round’s goal by +1 but Blue missed by 3. The result is -2 Stability.

Prototype Shown

What makes this so intriguing is that this financial precipice looming over everyone’s head doesn’t necessarily make Crisis a Semi-Co-Op game, where everyone has to at least partially collaborate to stave off total failure. Crisis provides room to play that way, especially on easier difficulty levels, but the game built in several strategically opportunistic situations where you may want the game to end prematurely. Because money and loans don’t factor into final scoring if the country goes bankrupt, for example, if you have the most VP and your chief competition is sitting on a ton of spare change, ending the game prematurely may be your best tactical move. It’s not a common or easily accomplished maneuver, but the fact that it’s possible at all in Crisis is a testament to the game’s design.

The land of Axia may be in significant trouble, but Crisis itself operates on very solid ground. Crisis is familiar without being derivative, blending straightforward worker placement mechanics with some clever twists to create a unique and replayable experience. Crisis is like if Viticulture had to deal with a grape blight or Tzolk’in ran out of corn. Thanks to a lot of moving pieces and numerous ways to gain points, Crisis admittedly does foster a slight experience advantage, but it doesn’t take extensive playthroughs for that to be quickly rectified. Between the looming issue of countrywide insolvency and competition from other players, Crisis offers as much of a challenge as you’re willing to risk. Every time through the game is fraught with difficult choices and scores that can fluctuate as often as the turn order. In Crisis, forget about doing all the things you want to do – you’ll often barely have the time to do all the things you need to do.

In the world of Axia, the future is uncertain. Hopefully the Axia in our world fares a little better. As it happens, we hear they’re eager to talk to foreign investors. If you think you have what it takes to salvage Axia from financial ruin and make a name for yourself in the process, then head on over to its Kickstarter. The future of Axia is in your hands.

[sc:Preview-Sealer ]

Photo Credits: Crisis cover and artwork by LudiCreations; Austerity Sign by Prudent Press.